An Interview with Dr. Joshua Lewer, Chairman of the Economics and Finance Department at Bradley University

Welcome to Peoria Magazine’s Econ Corner, a recurring feature in which we pose questions to experts about various economic issues and how they affect our lives and careers here in central Illinois. This month’s participant is returning contributor Dr. Joshua Lewer.

Peoria Magazine (PM): Please discuss the primary causes of ongoing social and income inequality in the United States and what effect it has on the overall economy. Meanwhile, beyond the moral component of such inequality, are there personal, practical implications for the

“haves” regarding the general health of the “have nots”?

Joshua Lewer (JL): Income inequality has been an important topic throughout human history. The Greek philosopher and historian, Plutarch, stated: “An imbalance between rich and poor is the oldest and most fatal ailment of all republics.” He observed that the survivability of republics and economic welfare of populations were a function of financial distribution.

So, what are some of the root causes of income and wealth inequality today? This is a multifaceted issue with many core exacerbating determinants. While not a universal list, here are some individual and societal factors driving income divergence:

1. Ability: There is no doubt that people have different mental, physical and aesthetic talents. Some of these abilities, such as IQ, can be inherited and are needed for high-paying jobs such as health care, law and corporate life. Some individuals have significant self-drive and motivation to succeed and harness these efforts to start their own businesses. In their best-selling book The Millionaire Next Door: The Surprising Secrets of America’s Wealthy, Thomas J. Stanley and William D. Danko report that 80 percent of millionaires in the United States are hard-working small business owners who live below their means and accumulate wealth by saving. Mental, physical and psychological endowment variations have a role in income inequality.

2. Picketty’s Forces of Divergence: In his best-selling book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty presents the spectacular increase in earnings of top managers across the world. In the United States, for example, the average yearly executive compensation for the top 500 companies was $12.3 million, or 354 times the average yearly compensation of rank-and-file workers of $35,000.

3. Educational Attainment: We are now living in the “New Economy” or “Knowledge Economy,” which is characterized by its speed, capital dynamics, networking and big data processing. The major form of wealth is rapidly becoming what economists call “human capital,” the developed ability of a person to produce in the economy. At the same time, the country is experiencing severe shortages of skilled workers and general labor.

The market forces of today and in the future will likely further exacerbate income inequality as the talent gap for higher skilled and semi-skilled workers will remain. The Bureau of Labor statistics monthly jobs report captures some of these labor demand imbalances. They have consistently reported that unemployment rates for those with higher educational attainment and skill sets are significantly lower than for those workers with less education and skills.

4. Sprawl: It’s pretty easy to identify the negatives of suburban sprawl. They include but are not limited to long commute times, heavy energy use and the pollution it brings, time cost, reduction of productive farm acres, redundancy of infrastructure and institutions, etc. As individuals and families leave one area for another with either real or perceived differences, they unknowingly hurt the social and income mobility of those they leave behind. The economic literature bears this out with many studies showing that peer effects — both peer quality and peer behavior — are among the most important determinants of economic and social outcomes.

A study by the Equality of Opportunity Project finds that “areas with a smaller middle class had lower rates of upward mobility,” and that there is a “significant negative correlation between residential segregation — different social classes living far apart — and the ability of the poor to rise.” The study finds that large portions of the southeastern part of the United States, led by Atlanta, have extremely low-income mobility rates due to suburban sprawl and the lack of public transportation from the low-skilled areas to where the jobs are.

There are other important determinants of income inequality such as skill-set agglomeration, asymmetric growth, discrimination and globalization issues, but I think we all understand that higher inequality negatively affects human welfare and GDP growth both in the short and long run.

PM: The Gini Coefficient, or Gini Index, is a measure of income and wealth inequality, with 0 equaling perfect equality and 1 equaling maximum inequality. On that scale, the U.S. now sits at .485, which makes it “the most unequal high income economy in the world,” topping the other G-7 nations. Meanwhile, inequality in the U.S. is at its highest point in 50 years, according to the Census Bureau, with the top 20% of earners taking in more than half of all American income.

Why is inequality so much worse in the U.S. than in most of the modern world? And, what have been the most effective remedies for income inequality and its attendant consequences?

JL: That’s correct. Today, economists measure income inequality by comparing the proportion of total income captured by various income cohorts. The Gini Coefficient is a useful inequality measurement that can be calculated across country and time to observe regional and country-specific trends. By dividing the population into equally sized 20% groups, we can observe what fraction of national income is going to each quintile cohort. What we are observing in the United States is a slowly rising Gini Coefficient trend that suggests the lower quintile groups are receiving less total national income while higher quintile groups are gaining an increasing share.

Similar to the causes of inequality, there is no one agreed-upon reason why the U.S. seems to be underperforming other G-7 countries on the inequality front. If there was a simple and unifying solution, it would seem reasonable that such a policy be undertaken. Many authors from the fields of sociology, political science and economics are researching this very question.

For there to be any chance for inequality improvement, our society must

improve our social and income mobility rates back to historic levels — that is, increasing the likelihood of someone from the lower to lower-middle quintile income class being able to jump to a higher economic standing in both relative and absolute terms.

Several years ago a team of leading economists embarked upon a major study on income inequality and mobility, now entitled Opportunity Insights (opportunityinsights.org). The work goes on today, but here are several key findings:

1. Segregation and Sprawl: Opportunity Insight authors state: “Areas with larger black populations tend to be more segregated by income and race, which could affect both white and black low-income individuals adversely. Indeed, we find a strong negative correlation between standard measures of racial and income segregation and upward mobility. Moreover, we also find that upward mobility is higher in cities with less sprawl, as measured by commute times to work.”

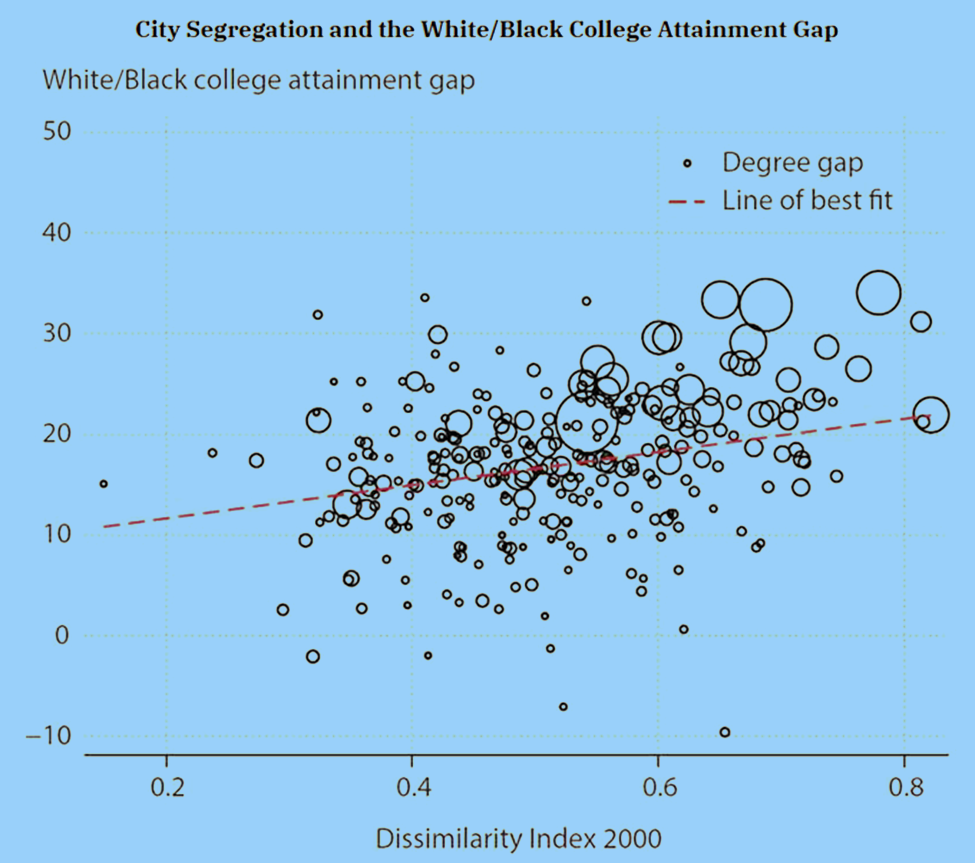

Using the Opportunity Insights data, St. Louis Federal Reserve economists Rubinton and Isaacson (2022) provide insights on the education or skill set channel through which segregation impacts inequality. They calculate the probability of earning a college degree for children born in the United States between 1978 and 1983 based on how segregated or “dissimilar” a particular community is. The chart above illustrates a positive relationship between the white/black college attainment gap and how segregated (or similar) a particular community is. Rubinton and Isaacson state, “Segregation mechanisms such as redlining are no longer part of the legal framework of U.S. cities, but the legacy of that segregation continues to affect children.”

2. Public School Quality: Regions within the U.S. where K-12 public schools had higher test scores and lower dropout rates, after controlling for income levels, necessarily had smaller class sizes. Importantly, the authors found that “areas with higher local tax rates, which are predominantly used to finance public schools, have higher rates of mobility.”

3. Social Capital: Regions within the U.S. with high community involvement and social networks have elevated mobility. Mobility is associated with greater participation in Parent-Teacher Organizations, local civic organizations, volunteerism, and religious activities. This finding reinforces the themes of other authors who find that strong families and community involvement can reverse the tide on rising inequality.

4. Family Structure: Opportunity Insight authors report that the “strongest predictors of upward mobility are measures of family structure such as the fraction of single parents in the area. As with race, parents’ marital status does not matter purely through its effects at the individual level. Children of married parents also have higher rates of upward mobility if they live in communities with fewer single parents.”

Lastly, factors that did not seem to make significant improvement in income inequality may surprise some. The researchers find that higher taxes on the affluent and larger tax credits for the poor have only marginal effects. Also, the number of local colleges and tuition rates had no correlation with mobility rates.