A new biography and companion website shine a light on his life and times.

Right or wrong, it’s often only after death that one’s legacy can be fully appreciated, which seems to be the case for Richard Pryor in his hometown. But wherever one looks, it appears that time has come.

With the tremendous success of “A Night for Richard”—hosted by the Peoria Civic Center in November and featuring six of the world’s most popular comedians—fundraising efforts for Preston Jackson’s sculpture of the Peoria native came to a successful conclusion. This followed the 2013 release of the Richard Pryor: Omit the Logic documentary, filmed partly in Peoria, and publication of another Pryor biography, Furious Cool, as well as last August’s announcement that Mike Epps would depict the comedian in a long-in-the-works biopic, with Oprah Winfrey in the role of his grandmother.

Meanwhile, in December, the most thoroughly researched Pryor biography to date hit bookshelves across the country. Becoming Richard Pryor shines a light on the comedian’s early years—ever elusive to biographers, coated in mystery, half-truth and legend. Eight years in the making, the book arrives courtesy of Scott Saul, professor of English and American studies at the University of California, Berkeley and award-winning author of Freedom Is, Freedom Ain’t: Jazz and the Making of the Sixties.

“As a young kid, I thought Richard Pryor was hilarious,” he recalls. “But behind that recognition was something else… the sense that the characters he played opened up on a world I didn’t know about—but that I needed to know about if I wanted to understand the larger world I was living in.

“There were so many layers to what he was doing. As I grew up, I grew into those different layers,” he continues. “I still don’t know if I’m up to understanding all the layers… The way he held very complicated emotions in suspension makes him infinitely complex. He didn’t go for cheap and easy resolutions.”

Peoria Was the Key

Despite his own memoir and numerous biographies over the years, Pryor’s life—particularly his earliest years—remained ripe for a definitive telling. “Peoria was the key,” Saul declares. “His upbringing in Peoria was the secret to his way of looking at the world. It was also a world he was running away from. So it was both the foundation of his life and a set of experiences that pushed him to the stage and out of Peoria.”

Yet it’s a story that’s never been fully told, its existence obscured in “a world that was trying to escape documentation,” Saul explains. When earlier researchers came to Peoria to uncover this story, they were largely rebuffed by Pryor’s friends and family, who were unwilling to reveal much of substance. Years later, Saul found enough time had passed for his own efforts to bear fruit. “When I visited Peoria, I found this very strong recognition that Richard Pryor was an important person to so many, and that for him to be well understood, people needed to be open about the world he had grown up in.”

Through years of exhaustive research, Saul was able to demystify Pryor’s childhood, sorting the truth from hearsay. Having interviewed more than 80 people and unearthed school records, Army files, family photographs, newspaper articles and more, he provides a historical depth that was missing from previous biographies. In Becoming Richard Pryor, it all comes together—scattered bits and pieces of Peoria history woven into an intricate quilt as complex as its subject.

Far removed from the old vaudeville joke about a bland Midwestern city (“Do you know Peoria?” “Oh, yes—I spent four years there one night.”), Pryor’s hometown emerges as a city of contrasts—“divided geographically and culturally between its industrial valley and the bluffs… between those who loved ‘Roarin’ Peoria’ and those who wanted to clean it up, between those who supported segregation and those who battled against it. There were always many Peorias within Peoria, and even within ‘Richard Pryor’s Peoria.’”

A Childhood Defined

His birth at St. Francis Hospital on December 1, 1940 yielded no announcement in the local papers. Richard Pryor came into the world marginalized—like all of Peoria’s black residents, then just three percent of the city’s population. He grew up in the red light district along North Washington Street, its assortment of taverns and brothels fueling the underground economy that provided for his family—and provided him the larger-than-life characters and stories he would later wield on stage.

In Saul’s book, we find a young, skinny Richard Pryor, bullied on the playground, connecting with classmates only through his wacky routines. We watch him bounce from school to school, forever searching for a fresh start. We see a child who always wanted to be included, who at one point asks: “Why did I have to be born black?”

We learn of the sixth-grade teacher who pushed him in the right direction and read about Carver Center—“the nurturing home Richard never had”—where Miss Juliette Whittaker took him under her wing, on field trips to local plays and to Lakeview Museum. We find young Richard in the seats of the Madison, Majestic and Rialto theaters, daydreaming of stardom, the heroics of Lash LaRue and John Wayne on the big screen. There he is: tangling with Mr. Fink at Central High School, shining shoes at the Hotel Pere Marquette, hopping on stage at Harold’s Club, cracking jokes at Collins Corner.

To search for Richard Pryor’s Peoria today is mostly to pore over old photographs and newspaper clippings—many of the buildings that defined his childhood exist only there. “One thing I really got a sense of… was just how much of Richard Pryor’s Peoria was paved over,” Saul notes. “I think [he] lived in six different places by the time he was 14, and none of those structures exist anymore. You get a sense of how ephemeral things are—especially for people who don’t have a lot of means to build monuments to their history.”

Indeed, the post-war Reform movement extinguished nearly every aspect of Pryor’s Peoria. The 1945 defeat of Mayor Nelson Edward Woodruff—whose toleration of vice helped earn the city its reputation as a “wide-open town”—signaled the beginning of the end, as a new generation of leaders swept away the underground economy of old Peoria. In the early fifties, the 300 block of North Washington, where the Pryors lived, was demolished, clearing the way for an interstate highway running right through the old red light district.

The Biographer’s Journey

Having uncovered a trove of historical documents, and with so many people opening up to him, the biographer was able to determine just how much truth resided in many of Pryor’s tales. “He turned his life into art, and art obeys different rules than history,” Saul declares. “But what I found, again and again, is that he was generally a reliable narrator. There was a germ of truth in the stories he told, but they were usually more multidimensional and more fascinating than either he revealed—or that he knew.”

Reflecting on a 1979 performance in which Pryor describes being beaten by his grandmother, Saul notes, “That’s an interpretation of something he remembers having happened to him; it’s shaped by many factors. It reveals more about how, in that moment in 1979, he is understanding that experience and translating it into performance. What you need as a biographer are all the different kinds of corroboration that will allow you to flesh out: who was this grandmother, and what was the nature of her relationship to him?

“When you go into the historical record… here’s a [newspaper article] from 1929 where the grandmother goes into a confectionary in Decatur, Illinois, and wallops a store owner for having slapped a black boy. You begin to see what Richard Pryor was talking about—the righteousness of his grandmother, the fierceness… well, here it is in the historical record. And you’ll find many more incidents like that.”

In other instances, Pryor appears to have misremembered pivotal events—his parents’ divorce proceedings, for example. “He always remembered that he betrayed his mother… that his testimony was the reason he was sent to live with his grandmother and father in Peoria, as opposed to his mother in Springfield. He remembered that he was 10 years old… that he was coached in his testimony by his grandmother, and he was so scared of [her], he betrayed his mother. But when I dug up the actual divorce documents, I realized it was something far different.”

His mother did not abandon him, Saul declares. “She tried to get him out of the red light district and bring him to Springfield… There’s no record that he was asked to give any testimony, or that it had any effect on the judge’s deliberations. And he was only five years old!

“The real story was so much more revealing and complicated—it suggested a battle for the custody of Richard. In the end, the grandmother won, but not because his mother was unwilling to fight for him. It made me think about how Pryor took on a lot of anguish and self-loathing in his life. He blamed himself, but he didn’t have to.

“That’s the complexity of history as opposed to fable,” he concludes. “The full truth is more bracing and complex—and more revealing. It happened again and again.”

Opening Up the Archives

As Saul researched his subject, the local history of Pryor’s hometown captivated him. “I couldn’t get enough, but I really had to cut back on the stuff about Peoria… because I had so much material.” Though excised from the book itself, much of that material lives on at BecomingRichardPryor.com, a companion website focused squarely on the Peoria Richard Pryor knew.

A unique repository of more than 200 documents from Saul’s research, the site brings to life Peoria’s transformation from “Sin City” to “All-America City,” placing the comedian’s early years against the backdrop of that larger historical narrative. Not only are the site’s tales captivating, so is its structure, which cross-links the people, places, eras and themes that together comprised Richard Pryor’s Peoria. True to its aim of opening up the biography for the digital age, Saul believes there are few other websites that contextualize a specific person, place and time within the larger tides of history in such a highly curated way.

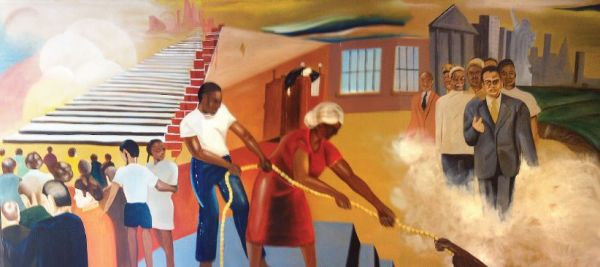

More importantly, the website extends the life of the documents he compiled, opening them up to the world. He cites a mural in the Carver Center auditorium that Pryor faced when he performed there—a complex social statement combining images of black empowerment with the trials and tribulations underlying the pursuit of freedom: most strikingly, a white judge who appears to have fallen asleep at the bench. “There was a big gap, it seems, between the promise of the Statue of Liberty and the reality of justice in America,” Saul writes.

With no room for this story in the book, it exists online, “where people can actually see the mural and read my commentary on it,” he notes. “They can read about the artist and learn something about that late ‘40s moment when it was painted. It’s great to have—it’s not lost; it’s not just on the cutting-room floor.”

Reconciling an All-America City

This spring, an eight-foot Richard Pryor, cast in bronze, will peer down from the corner of State and Washington, just a few blocks south of the former red light district where he grew up, for better and for worse. As the city works to revitalize its downtown and recapture the energies of daily life that once existed there, Preston Jackson’s marvelous statue is another piece of the puzzle.

Considering Peoria’s first All-America City designation, in 1953, stemmed directly from the Reform movement that paved over Richard Pryor’s Peoria, it’s no small irony that the city captured a fourth All-America title just as momentum for honoring the legendary comedian was building to a crescendo. Saul believes these two Peorias can be reconciled—that Peoria is an All-America City not just for its “shiny, happy surface,” but for the very history some have wished away.

“The cover of my book features the colors of the American flag—that was a design I pushed for,” he explains. “I think the story of Richard Pryor stretches American history into a new shape. It’s still an all-American story, but it’s a much more complicated one. He dealt with serious, psychic pain—physical and emotional—and took an unflinching look at all that. He looked at it in other people, in communities, and especially within himself.

“To me, that’s where you get the ‘all’ in All-American—in looking at the ‘all.’ You’re not just looking at a fraction and trying to pretend it’s the whole thing… If you look at the story of Richard Pryor and think about all the forces that collided in his life, you get a pretty complicated picture of what was happening in Peoria at the time… this mixture of high and low, rich and poor, the powerful and the outcasts. That’s how much he encompasses.” a&s

For more information, visit BecomingRichardPryor.com.