When National Endowment for the Arts Chairman Rocco Landesman visited Peoria last fall, one of his first stops was the large warehouse at the corner of Walnut and Water streets. Roaming its hallways were potters and painters, sculptors and printmakers, photographers and other artists whose working studios have come to define the old industrial building—known widely as the Murray Building, and more recently dubbed the Murray Center for the Arts.

“We felt it was important for Rocco to see the building, because it is really the best example of what could happen in the Warehouse District,” explained Jacob Grant, a ceramic artist whose studio is on the fourth floor of the giant structure. “The Murray is nothing different or new in the whole scope of things—cities around the country have been doing similar things for a long time. But it is really the best example in Peoria.”

Across its eight decades, the building evolved from its manufacturing and warehousing origins, first into a downtown retail hub, and then into a haven for artists—the largest assembly of artist studios in central Illinois.

From Factory to Retail

“Peoria’s productive industries have been the source of her greatness, and prominent among the commercial concerns of this character is the great Stuber & Kuck tinware factory,” noted the 1912 publication Peoria: City and County, Illinois. “There is no kind of tinware or tin product which the Stuber & Kuck factory does not make.”

Joseph Stuber and his partner, Henry Kuck, formed the business in 1887. Its main plant was located on S.W. Adams Street, but with continual growth came the need for more space. In 1928, the manufacturer contracted to build a four-story warehouse and factory building on the east corner of Walnut and Water streets. Upon the dissolution of Stuber & Kuck, the building at 100 Walnut Street was retained by Stuber and became known as the ‘Stuber Building.’

The ensuing decades found the building playing host to a wide variety of businesses. “My father [George Murray, Sr.] originally leased the building from the Stubers,” said George Murray, the building’s current and long-time owner. For many years, the senior Murray operated the George Murray Tire Company out of the first floor. On the fourth floor, an assembly line worked sewing machines for Boss Manufacturing, fabricating its line of protective gloves. At one time, more than $1 million of Seagram products were stored on the second floor in a space leased to Federal Warehouse Co.

After leasing for many years, Murray purchased the building in the early ‘60s, and the shift from manufacturing to retail continued. After the tire company closed, the Murrays operated a catalog showroom store out of the building for some time, but it eventually went out of business as well. The building sat empty for awhile, until 1986, when Dan and Kim Philips opened the Illinois Antique Center on the second floor.

Warehouse on Walnut Street

Warehouse on Walnut Street

About that time, the Philipses told their friend Pete Kelley, a passionate advocate for the arts, about open space available at the Murray Building. “When we opened the Antique Center,” said Dan Philips, “we realized there was a strong link between antiques and art, both in the appreciation of the form and function, and in the history. We felt there was a connection there.” The following year, Kelley brought his vision of an art gallery with artist studios into the building.

“This was something I’d always wanted to do,” recalled Kelley. “At that time, the arts were not really downtown at all.” So with the Antique Center below him, he set up shop on the third floor, opening Waterfront Studios and Gallery in 1988. Waterfront offered artist studios, classrooms and a gallery, hosting shows, fundraisers and performance art in its three-year existence.

Meanwhile, plans at the time called for a retail mall to be developed in downtown Peoria that would run from the Sears Block south to the Franklin Street Bridge, near the Murray Building. “We thought that if there was going to be mainstream retail in close proximity, specialty shops would be a good thing,” said Philips. From that notion, a marketplace began to evolve on the first floor—now rebranded the Walnut Street Warehouse—which included an Irish gift shop, book and toy store, jewelry outlet and sandwich shop.

Now the building was operating on three floors, with arts on the third, antiques on the second, and mixed-use retail and a restaurant on the first. The Antique Center and specialty shops brought a steady flow of traffic, which was fed by gallery openings and other events at Waterfront. “It had a really nice synergy to it,” recalled Philips. This blend of retail, art and antiques operated for a number of years in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s.

Laying the Groundwork

One of the first artists to take up residence at the Murray was the renowned Preston Jackson. Jackson was friends with Kelley and the Philipses, who informed him of the available space. Upon moving in, his large studio became a hub of activity, and Jackson, the Philipses and Kelley’s Waterfront Studios, formed a “kind of family in the building,” said Philips.

Half a dozen other artists had smaller workspaces at Waterfront, for whom Jackson served as a de facto mentor. At the same time, he was at work in his own studio on one of his most famous commissions—the massive bronze murals that serve as the facade and entry/exit doors at the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, east of St. Louis.

Eventually, however, the economy went south, and in 1990, Kelley closed Waterfront. Though it only lasted several years, it was an important piece of Peoria’s cultural fabric, helping to lay the groundwork for the Murray Building’s niche as a hub for artists. Not long after Waterfront closed, Jackson expanded his studio and eventually opened his own Round River Gallery in the building. Likewise, the Antique Center continued to expand, even as plans for the downtown mall were shelved and the storefronts on the first floor closed their doors.

By the mid-1990s, the Antique Center occupied two entire floors of the building. It was getting expensive to pay rent on 40,000 square feet, and so the Philipses began looking for a building to purchase. After eight years at the Murray, they moved the Antique Center down the road to its current location on Water Street, while Jackson and his partner, Bob Emser, opened the Contemporary Art Center and Checkered Raven Gallery next door. The arts were expanding downtown.

The Arts Blossom

“We ended up with a lot of space,” said George Murray, “and the artists started coming in.” On the heels of Preston Jackson and Pete Kelley’s Waterfront Studios, a range of working artists moved in and out of the building throughout the 1990s. A number of students and faculty from the graduate art program at Bradley University took up space there, a connection that continues to this day.

A dance school. A taxicab company. A photography studio. An advertising firm. All types of organizations have taken up residence at 100 Walnut Street over the years. And while artists have had a strong presence since the late 1980s, the building has really blossomed into a center of artistic activity over the last six years.

Jerry McNeil is a full-time clay artist, operating McNeil’s Pottery out of his third-floor studio since 2002. “I started in a basement, moved to a garage, and from there, I simply got tired of tripping over lawnmowers and hoses and garbage cans,” he laughed. “The [creative] process was just taking too long…I decided that if I was really going to get serious, I had to get into a dedicated studio space.”

Jerry McNeil is a full-time clay artist, operating McNeil’s Pottery out of his third-floor studio since 2002. “I started in a basement, moved to a garage, and from there, I simply got tired of tripping over lawnmowers and hoses and garbage cans,” he laughed. “The [creative] process was just taking too long…I decided that if I was really going to get serious, I had to get into a dedicated studio space.”

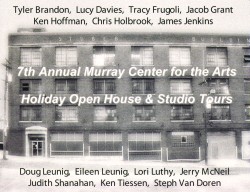

In 2003, McNeil held an open house in his studio at the Murray, the first of what would become an annual event to increase awareness of the building’s artists. For several years, it was primarily a solo venture, but as more artists took up space, the open house grew as well. Last December marked the seventh annual open house, featuring 14 resident artists in conjunction with a holiday gift show at the nearby Peoria Art Guild. The event has become a favorite of arts lovers, offering a peek into the working environments of many of Peoria’s finest artists. “Opening [the building] up enables people to come in and see the life inside,” said Lucy Davies, a sculptor, painter and McNeil’s wife, who has her own studio in the building.

The Space Within

If not for its unique niche, the building at Walnut and Water might be just another aging industrial structure past its prime. But as the great architect Frank Lloyd Wright once expressed, “The space within becomes the reality of the building.” And when that space is devoted to the creative work of artists, it takes on entirely new dimensions.

Over the years, the building’s expansive floors have been broken up and its space carved out in a myriad of arrangements, as tenants come and go. A businessman by trade, George Murray, with his son Brian, has come to embrace the role of providing affordable studio space for artists, and strives to project a family-like atmosphere. “He enables us to be here,” notes Davies.

Over the years, the building’s expansive floors have been broken up and its space carved out in a myriad of arrangements, as tenants come and go. A businessman by trade, George Murray, with his son Brian, has come to embrace the role of providing affordable studio space for artists, and strives to project a family-like atmosphere. “He enables us to be here,” notes Davies.

“He’s like my second dad,” added the sculptor and painter James Jenkins, who has occupied space in the building since the mid-‘90s. “We’ve had this relationship for so many years…you just become part of the family.”

And the Murrays are keen to ensure that incoming tenants will fit well within this “family.” “Most people come to us and tell us what they want to do,” said George Murray, “and if we feel that they will complement the other people in the building, then we will try to work something out.”

The Murrays are generous with their time and resources in helping tenants develop their desired workspaces. Most of the building’s artists have a story or two about George or Brian helping them out—hauling materials, repainting floors and walls, among other renovations. This makes sense for everyone—the artists are happy, and turnover is low. It also keeps maintenance costs down, as tenants are well invested in keeping up their space.

Crafting an Environment

“When I moved to the Murray, I had to tear out the old floor and refinish it,” said Jacob Grant. “I painted the studio and designed and built my work tables, ware racks, spray booth and photo area.

“My space helps me create, for a number of reasons,” he continued. “I do not have the space to work at home effectively. I am also not very productive when I have my workspace in the same location where I live—too many distractions when I should be working.”

“A good environment is essential to productive creative work,” declared portrait/landscape artist Ken Tiessen, who shares a studio with oil painter Tracey Frugoli. When they moved in three years ago, the space was a mess. Over the course of several weeks, Tiessen patched and painted the dilapidated walls and ceiling, installed baseboard and trim, sanded and painted the floor, redid the entry door and reworked the lighting. Seeking to expand when their neighbor moved out, he repeated the process all over again. “It is still remarkable what a difference that hard work made,” said Tiessen.

“[It] created a place where I can work easily, comfortably and safely,” he added. “It is a place where I can bring my extensive art materials and have them be clean, safe and easy to get to—a place that does not intrude on my state of mind. That allows me to focus on what is important—the next piece of art, the next stroke of the pastel. To work, study and paint in relative peace and quiet.”

“[It] created a place where I can work easily, comfortably and safely,” he added. “It is a place where I can bring my extensive art materials and have them be clean, safe and easy to get to—a place that does not intrude on my state of mind. That allows me to focus on what is important—the next piece of art, the next stroke of the pastel. To work, study and paint in relative peace and quiet.”

Tyler Brandon, a ceramic artist and recent Bradley graduate, took up space in the Murray Building last year. “I’ve done a lot of work creating an environment that I thrive in,” he said, “and the studio itself has become just as much a work of art as the pieces being created within it. Whether I’m making pots or relaxing in my hammock figuring out what materials need to be in my next order, the space certainly has helped push my creative process.”

Fuel for Creativity

Whether working at home alone or in a clustered environment with others, artists treasure their workspaces, and no two are alike. “Every studio in the building is as unique as the artist within it,” confirmed Brandon.

Mixed-media artist Judith Shanahan shared a smaller workspace at the Murray in the late ‘80s, where she learned sculpture from Preston Jackson. She moved back into the building about 10 years ago. Her studio is a cozy, 650-square-foot space with a folksy, “home-away-from-home” charm—and the only one with a loft. “My husband and I can take a siesta on an inflatable mattress when we have to spend long hours in town,” she said. “I can turn on my radio, listen to jazz on WGLT and feel inspired. I get lots of ideas, make notes to myself, and feel very productive with supplies at my fingertips.”

The building’s industrial nature is a good fit for Shanahan. “It is a great benefit having both a passenger elevator and a freight elevator for hauling supplies and equipment in and out,” she said. “[And] with nothing fancy on the floors, I don’t feel guilty if paint gets dripped…I just wipe it up and keep going.”

Ken Hoffman appreciates the roominess of the 3,600-square-foot studio in which he has worked since 2000. “I just love that space,” said the veteran painter. “It’s safe and secure, and the light is fabulous. I’ve got three enormous walls for my big 8×12-foot paintings, and adequate storage space when I finish my work. It is the best space I’ve had since I’ve been working as an artist.”

Eco-artist Steph Van Doren originally worked in a studio provided by Bradley University as part of its graduate program. She moved down the hall to her current space after graduating last May. “I love the multitude of windows and the amazing light that my studio offers,” she reflects. “I enjoy standing at my window that faces the river, drinking coffee and watching the barges go by. It fuels my creative soul.”

The Door Is Open

From generating ideas to offering critique and guidance, artists tend to benefit from the close contact with other artists nurtured in a shared work environment such as at the Murray. “It helps build synergy,” notes Jacob Grant.

“One of the reasons I stayed in the building after graduation was the amazing opportunity to work surrounded by so many other creative people,” added Van Doren. “I have had many opportunities to hang out and talk with like spirits about art, contemporary issues, etc. It has an energy you cannot find anywhere else.”

Tyler Brandon agrees. “For me, just getting out of school and trying to establish myself as an artist, it has been a great thing to be around other artists that are already established and working independently,” he said. “I generally leave my door open, and I almost always get a visitor or two. It really is a great place full of great people always ready to check out a new piece or give advice on a piece you’re working on at the moment.”

From time to time, some of the artists will get together for lunch or a beer in the evening, but “Mostly,” says Ken Hoffman, “we come there to work…This is a group that really concentrates on their work. Time is very important to us. I think people respect each other’s space and the time we put in.”

From time to time, some of the artists will get together for lunch or a beer in the evening, but “Mostly,” says Ken Hoffman, “we come there to work…This is a group that really concentrates on their work. Time is very important to us. I think people respect each other’s space and the time we put in.”

“In terms of the collective down here, we are by and large a group of very dedicated and professional artists,” adds Jerry McNeil. “This is my full-time job, and I’m fully dedicated to what I’m doing.”

A Center for the Arts

About eight months ago, some of the building’s artists were kicking around ideas to better define the building and its place in the arts community. From those conversations, the Murray Center for the Arts was born.

“Just calling it ‘The Murray Building’ did not seem to convey the message of the place focusing on arts,” said Jacob Grant. “By having the word ‘Arts’ in the title, people seem to take it a little more seriously.” The group is also looking into the possibility of incorporating as a not-for-profit organization.

With artist studios comprising most of the third and fourth floors, and the second floor mostly storage space, the street level is ripe for any number of possible developments—a coffee shop, wine bar, a small art gallery—which could work in synergy with the redevelopment of Peoria’s Warehouse District.

Downtown Renewal

Art breathes life into the neighborhoods in which it is prominent. Artists infuse an area with creative energy and can play a significant role in urban revitalization efforts—bringing vibrancy to a community, enriching the quality of life and developing the creative workforce that is a hallmark of the 21st-century economy.

“Historically, when a downtown enjoys a rebirth, the arts play a very important role in that process.” This sentiment remains as true today as when it was written into a business plan for Pete Kelley’s Waterfront Studios nearly 20 years ago. At that time, the arts did not have a significant presence in downtown Peoria, while many of the now-empty buildings just south of downtown still held functioning businesses.

Today, with the Art Guild and Contemporary Art Center to the northeast, and the newly-opened Meyers Block Fine Art Gallery and Prairie Center of the Arts to the southwest, a corridor—anchored by the arts—is slowly coming into existence, stretching from Main Street to the south end of the Warehouse District. The construction of the Peoria Riverfront Museum and pending announcement of a significant development project in the Warehouse District can only add to the momentum. And the Murray Center for the Arts is right in the middle of it all. a&s