Dr. George Zeller revolutionized mental health care there, and ‘still watches over the place.’

Most museums make it easy for visitors to drop by. But there aren’t any road signs directing you to the Peoria State Hospital Museum. GPS might not help much, either, since two different addresses are listed online.

But many area residents know where the Peoria State Hospital once stood. It was a big place in its day. You pass through Bartonville and peel off onto Pfeiffer Road. At the top of the hill is where the hospital once stood — 63 buildings sprawled over 200 acres. But that was a long time ago. Today, only 13 buildings remain. One of them houses the little museum with photos and artifacts covering hospital history from 1902 to 1973, when the facility closed.

The museum, which offers free admission from 2 to 5 p.m. on Tuesdays and Thursdays, retains items that were put on display in the hospital’s early days while providing a reminder on how not to treat mental illness: restraining chairs, leather muffs, anklets, wristlets and canvas straitjackets.

Christina Morris founded the museum in 2013. The Pekin resident, now 49, recalls first visiting the hospital grounds as a little girl. “It was a place for special people,” her grandfather told her. “There were roses, deer. I thought it was a beautiful place,” she said.

Morris continued to visit, noting that she was referred to as “the asylum girl” due to the amount of time she spent scouring the grounds as a teen.

“Some would call it an obsession,” she said. “I call it passion.”

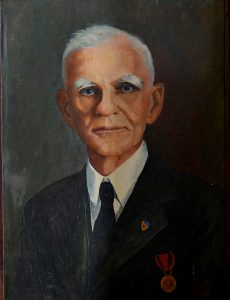

Pointing to a 100-year-old china hutch containing memorabilia at the museum, Morris cites hospital history chapter and verse, enthusiastically emphasizing the accomplishments of the hospital’s first superintendent, Dr. George A. Zeller, the Spring Bay native whose image is on prominent display here.

When the institution opened in 1902, it was known as the Illinois Asylum for the Incurable Insane. Patients were transported in chains and routinely locked up behind bars. Zeller changed that, said Morris.

Zeller had compassion and expected it of others. His employees understood the rules — to treat the patients with respect. The man was ahead of his time, she said.

Sylvia Shults, a circulation specialist at the Fondulac Library in East Peoria, is also fascinated by Zeller’s record. “His motto was let’s treat these people (patients) with kindness. The Peoria State Hospital was a premier institution not just in Illinois or the United States but in the world,” she said.

Along with unlocking doors, removing bars and abolishing the use of narcotic drugs, Zeller instituted an eight-hour day for employees and championed women at the institution, putting female nurses in charge. He also stressed a healthy diet for patients while rejecting uniforms.

“He got pushback on just about everything he did, such as establishing a nurses’ college on site where young women could come and be educated,” said Shults.

For a time, Zeller left Peoria State Hospital, returning in 1921 after a six-year absence. He was appalled at what he found, said Morris. “The first three days of his return he spent as a patient to better understand the conditions,” she said. “Even the staff didn’t know he had returned.”

Zeller retired for good in 1935 but the institution continued to be a compassionate place after his death in 1938, she said. “His methods hung on for a long time. There were movies for patients on Friday night and dances on Saturday. Whenever the Barnum & Bailey circus started coming to town in the 1940s, they set up on the hospital grounds,” said Shults.

At its peak in the 1950s, the hospital housed 2,800 patients. When state funding cuts led to reduced staff, problems followed, she said. “Instead of one nurse for every two patients, it was one nurse for 60 patients.”

Morris knows that heightened interest in paranormal activity has clouded the otherwise sterling record of Peoria State Hospital, and her group actively seeks to dispel public misconceptions about what happened on the Bartonville hilltop. There was no torture practiced there, nor were patients treated and buried as numbers, she said. Numbering grave sites was done for patient privacy, at a time when many families wished to avoid the stigma of having a relative in a mental institution.

As for the number of deaths at Peoria State Hospital, there were actually many more than the 4,100 buried there, said Morris. “The number one killer was tuberculosis, the number two killer was pellagra and the number three killer was old age,” she said. Many of those patients were buried in family plots elsewhere..

The museum offers other facts about Zeller and his contributions:

- Zeller’s father was also a doctor who came to this country from Germany as a young man.

- George Zeller volunteered for one year’s service as a U.S. Army surgeon in the Philippines while the asylum construction was underway. A cholera epidemic on the island extended his stay.

- Lorado Taft, the celebrated sculptor from Elmwood, was best man at Zeller’s wedding when he married Sophie Kline of Henry.

- Zeller purchased the grounds of old Jubilee College in 1931, which he later turned over to the state of Illinois.

- Zeller was so well thought of that, upon his retirement in 1935, he was offered an apartment — in the Bowen Building, the hospital’s administration building that also housed the nurses’ dormitory — where he lived until his death in 1938. He is buried in Peoria’s Springdale Cemetery. Meanwhile, his name adorned the local mental health center that replaced Peoria State Hospital until it, too, closed.

It’s important to remember Peoria State Hospital and Zeller’s work there, especially given the condition of mental health treatment in much of America today, said Janette Marie, a 39-year-old insurance agent who made a 20-minute documentary on Peoria State Hospital in 2015, for which she interviewed former employees including a doctor and several local historians.

“The asylums have closed… Homelessness is rampant. It all trickles back to this story,” she said. “We need to make people more aware of the situation.”

As for those supposed ghosts roaming the property, well, the man whose campaign against cruelty made Peoria State Hospital so notable remains on the case, said Shults.

“Dr. Zeller’s spirit is still on the hilltop,” she said. “He still watches over the place.”