Downtown Peoria Heights is one of those charming places where, if you were on vacation, you’d take a picture of it.

Even before the Heights became the area’s Restaurant Row, the tidy street of small shops, street planters overflowing with flowers and colorful awnings set it apart from other shopping districts as early as 1990.

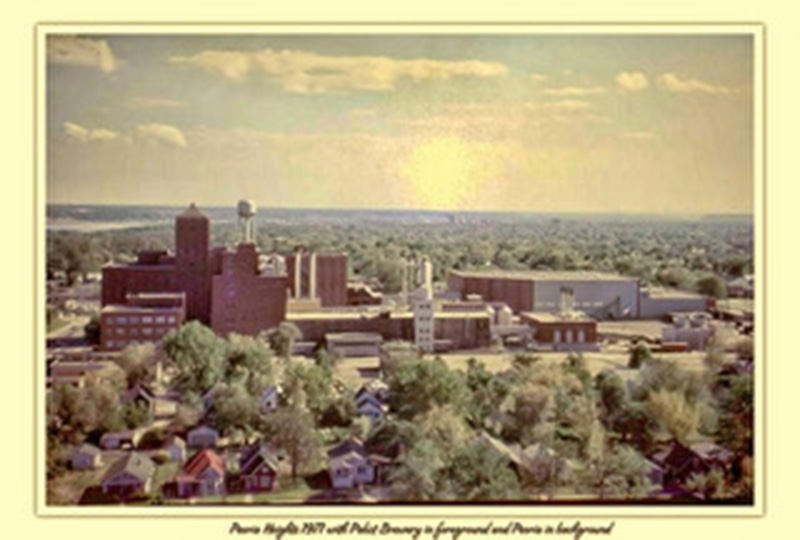

Photos from just 10 to 15 years earlier show a grittier town, a downtown that was more utilitarian than charming. But like most municipalities, Peoria Heights has been through its share of transformations.

This year, Peoria Heights is observing the 125th anniversary of its re-incorporation. The municipality was originally incorporated in 1895 as Prospect Heights. Three years later, the village was informed that another Prospect Heights already existed in Illinois and that other town had first dibs on the name. Oops. In 1898, the village was reincorporated as Peoria Heights, making 2023 the village’s quasquicentennial, meaning its 125th anniversary.

Following an initial celebration in September, two more quasquicentennial events remain, including a gala at the Peoria Country Club on Nov. 11, the actual date of the re-incorporation 125 years ago. said Barb Milaccio, president of the Peoria Heights Chamber of Commerce Board. The final anniversary party will be the Chamber’s Kringle Market in Tower Park on Dec. 1 and 2, highlighted by a tree-lighting, carolers and Santa’s arrival, said Milaccio.

The best views in the valley

Before there was a Prospect Heights in central Illinois, there was the Prospect Heights Land Company. Four investors created the company to promote their new subdivision east of Prospect Road and north of Glen Avenue, with a view from the bluff said to be among the most breathtaking along the Illinois River valley.

By 1892, the company had acquired more than 500 acres for its subdivision, valued at $186,000, which were offered at auction. Buyers’ comments reported in the local newspaper of that time indicate that even nearby residents were surprised by the stunning views from the bluff and saw the subdivision as perfectly situated for a summer home.

The developers had big plans for Prospect Heights, including a racetrack for what they hoped would become the permanent location of the Illinois State Fair.

They planned Prospect Park, with a hotel and summer resort built on 10 acres at Prospect Road east of Forest Park Drive. At an estimated cost of $5,000, the three-story structure had some 80 rooms. Immediately east of the hotel was a deep ravine over which a pavilion was situated, with a Hungarian orchestra nightly serenading the countryside. On the morning of Sept. 15, 1899, the hotel was destroyed by fire, taking with it the plans of the Prospect Heights Land Company, which never materialized.

For fine dining and convivial company, Doc Gray’s Ye Olde Tavern was the place to go during the late 1890s and early 1900s. Located at the corner of Prospect Road and Grandview Drive, the building was described as “picturesque” and “palatial.” Owner Charles Gray was known as a gracious host with many friends, but Ye Old Tavern fell victim to Prohibition. One evening, the place was raided by federal agents. The death knell came Nov. 20, 1920, when fire destroyed the tavern.

An industrial past

At the time of the incorporation and re-incorporation of Peoria Heights, manufacturing was booming in the community.

Between 1896-97, the Rouse and Hazard Company built a bicycle factory on the east side of Prospect Road, south of the Rock Island and Peoria railroad tracks, employing up to 150 people. Here the company manufactured the Sylph bicycle with the then-novel, easy-riding knee action, designed by Charles E. Duryea — yes, one of those Duryeas of automobile fame — of Wyoming, Illinois.

Monroe Seiberling built a factory on the southwest corner of Prospect Road and Seiberling Avenue in 1895-96, which housed the Peoria Rubber and Manufacturing Co., making bicycles and balloon tires. The balloon tires prompted Duryea to design a new bicycle, eliminating the knee action and introducing the first drop-frame-style bicycle, also known as a lady’s bicycle, which became quite popular. Here, the company also made 18 Duryea automobiles, the nation’s first gasoline-powered vehicles.

Seiberling’s factory employed 600 people, making 10,000 bicycles and 25,000 pairs of tires a year. In about 1898, Seiberling and Duryea reportedly had a falling out and Duryea moved to Reading, Pennsylvania, where he continued to manufacture his automobile.

The Smithsonian Institute has the first gasoline-powered automobile ever built in America, or more precisely, built in the Village of Peoria Heights.

John B. Bartholomew took over the buildings at Prospect and Seiberling and began assembling the Glide automobile. At full operation the plant’s yearly output was 175 cars and continued until World War I. After the war, Glide trucks were manufactured at the plant until 1920.

We want beer, doggonit

The next industry to take up residence at Prospect and Seiberling was Premier Malt Products in 1924, making maltose syrup used in cooking and home brewing. With the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, the following year the Peoria Heights plant started brewing Pabst Blue Ribbon beer and ale.

At peak production, the Pabst Brewery employed 1,000 people. Due to declining sales and money problems, the brewery was closed in 1982, putting 700 people out of work.

The population of Peoria Heights in 1980, two years before Pabst shut down, was 7,453. Today the population of Peoria Heights is 5,800. “There was a mass exodus of people in the ‘80s that we’re still recovering from,” said Heights Mayor Michael Phelan.

Nonetheless, the village has come a long way. Last year, Village Hall ran a $1 million budget surplus. Village trustees have lowered the municipal property tax levy the past three years.

As a lifelong resident, Phelan recalls Pabst Brewery as a huge fixture in the village.

“Growing up, we didn’t have air conditioning, so at night during the summer months you’d hear the trains constantly switching throughout the night, trucks idling, trucks pulling in and out. It was a three-shifts-a-day, very busy operation,” Phelan said.

Peoria Heights has always been known for the river that flows past it. “There was lots of fishing and lots of cabins along the river. The Illinois River produced more fish than any other river in the country, except the Columbia River,” said Phelan. “That was before they reversed the flow of the Chicago River, so then you didn’t have the pollution and siltation. The river was beautiful and clear.”

Today, Peoria Heights is trying to capitalize on that natural beauty and those amenities again by building a local economy not only focused on the hospitality industry — its Restaurant Row downtown is perhaps the most popular in the region — but on ecotourism and recreation, with its sights set firmly forward.