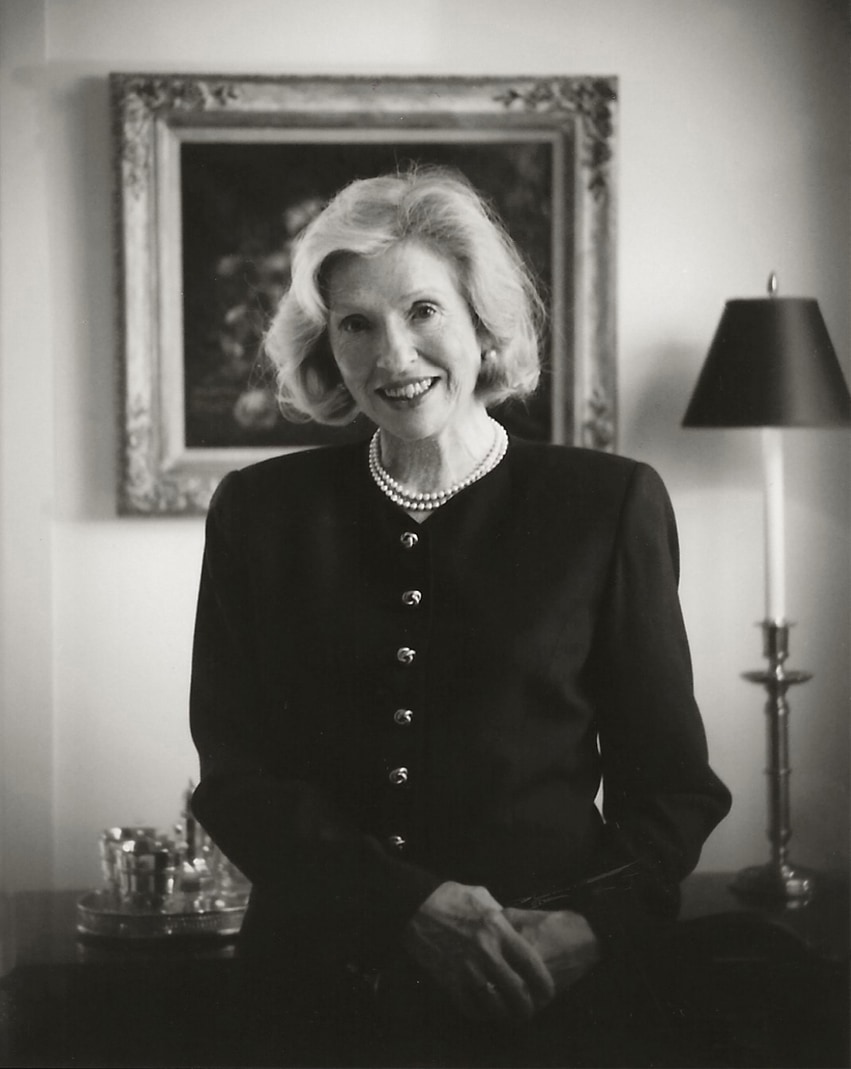

Growing up in Newton, Massachusetts, Esther Cohen understood the values of service and volunteerism from a very young age. Her parents were active in a wide range of community organizations, and she got involved in theater and music as a child, quickly learning the importance of art and culture to a community. These were lessons that stayed with her for life—and that she would apply here in Peoria.

Upon graduating from Smith College, Esther took a prestigious business course at Radcliffe College, the women’s counterpart to Harvard, which at the time accepted only men as students. When her father passed away unexpectedly, she put that knowledge to use running his real estate business—an uncommon leadership position for a young woman in the post-war 1950s. Around that time, she met a young man from Peoria who was attending Harvard Business School. She and Robert Cohen soon married, and the two moved from Boston to Peoria in 1958 with their young daughter Sheryl in tow.

While the Midwest initially presented a culture shock, Esther Cohen quickly grew her circle of friends—including many fellow alumni of Smith College—and embarked on a lifetime of community service. From the YWCA and Youth Farm League to the Peoria Art Guild and Peoria Symphony Guild, she was well-known for applying her energy, creativity, problem-solving abilities and motivation skills to dozens of nonprofit organizations and arts groups. Esther and a handful of her friends established many of these organizations, willing them into existence and ensuring their survival through their own tireless efforts. It was the “golden age of volunteering,” she explains, “and we all pitched in.”

When Esther received the YWCA’s Eliza Pindell Outstanding Achievement Award in the 1990s, a whopping 35 nominators attested to her intelligence, effectiveness, resourcefulness and hard work. Her thoughtful and sustained devotion to enriching the Peoria community were truly legendary. At a roast for her in 1975, the late Kathryn Timmes (a celebrated educator and Local Legend herself) noted the “fullness of life around Esther” and that her “drive extends to everything and everyone.”

Esther Cohen helped bring world-class opera to Peoria and represented the city to the outside world, serving as a director of Opera Guild International and a local representative on the Illinois Arts Alliance board. Today, her legacy passes on to the next generation through her daughters Sheryl and Jennifer, son Les, and two grandchildren.

Tell us about your family and childhood in New England. Where was your family from originally?

Both of my parents were second-generation Americans. My mother’s parents were Russian, and my father’s parents were from Austria. I am Jewish and wouldn’t be here today if the family had stayed in Austria. Obviously I’m very grateful that my grandparents made the wise decision to come here. My grandparents on my mother’s side settled in Newport, Vermont, up near the Canadian border, and my grandparents on my father’s side settled in Attleboro, Massachusetts.

My parents met through their work in the community. My father was in real estate partnerships with his brother-in-law during the Great Depression era. My mother was involved a lot in community affairs and many Jewish organizations. They were always going to meetings and were very active in helping organizations. I was born in 1930, so I was a child of the Depression. We were fortunate to have a lot of theater and concerts in New England, and I did all of those things.

Did your family struggle during the Depression years?

I guess we did. I was pretty young, so I was not too aware. My father built an apartment hotel in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and that was a struggle. There was a lot of stress he never told us about. But we made it through okay. I remember my father telling me, even though he was a Republican, he said that FDR made a tremendous difference when he declared, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” He believed that changed the whole atmosphere of the country.

You graduated from Smith College and then joined the Radcliffe business program. Tell us about your experience during those years.

My father was a graduate of Harvard, so he was interested in making sure I went to a good women’s college. All of my friends went to Wellesley, which was only 15 minutes from home; I chose Smith to be adventurous—it was 100 miles from home! I had a double major in history and art history. I was at Smith for four years and graduated in 1952.

My father was determined that I go into the business program at Radcliffe, which was sort of a sister school to Harvard. They weren’t letting women into Harvard Business School in those days, so the Harvard professors would come across the Charles River to teach us at Radcliffe.

There were 50 women in this program, and we all wanted to find more interesting jobs. I wanted to be an assistant vice president, which was all we could aspire to in those days. We had a training class for manual labor, and I went to the U.S. Rubber Company in Providence, Rhode Island, with another gal from the program. We stayed there for a month, and I wound golf balls. In order to make my quota, I would sing songs over the whirl of the machines.

What was that like?

There were six machines for each of us on the line. We would take the core of a ball and twist on a very thin thread of rubber, then put it on a machine to spin around and cover it all. I have a joint that’s still off-kilter from doing those golf balls!

After my second semester, another gal and I were assigned to go to New York. We lived at the Barbizon, which was a dormitory for women who were working or going to school. No men were allowed upstairs! I worked in the marketing research department for a big ad agency, J. Walter Thompson. This was a big step up for me. There were different assignments, and I learned many interesting things. I remember once they sent me out to interview people about whether they wanted vinyl or leather car seats. Eventually, the Radcliffe program helped me find a job as assistant personnel director at the University Hospital in Boston. I spent two great years there.

How did you use that experience in business school?

Well, my father must have had a premonition because he died of acute leukemia a few years later. Being the eldest, he left me in charge of the business, managing the apartment houses and commercial property. I think that’s why he wanted me to go to business school, so at least I would know something about business. I earned my certificate, and thank goodness I had that! I got to know which side of the ledger the credit side was on, and how to look at a balance sheet. And it helped me to know what questions to ask.

So you were running your father’s business in your early twenties. That must have been very unusual for a woman at that time!

Yes, they wrote me up in the newspaper. It was either the Boston Herald or the Boston Globe.

Were you treated differently as a woman in business?

Well, yes. One winter everything froze, and we couldn’t get enough heating oil for the buildings. My tenants were cold and upset, and I couldn’t get anyone from the oil company to answer my calls! I felt so badly for them. I’m sure if my father was alive, they would have done whatever he asked, but I couldn’t get any attention at all. They were surprised when I switched oil companies.

Wow, that’s terrible!

It absolutely is, but it’s true. And I’m sure other women were treated the same. I never got a complex about it, though. I think that’s just the way it was.

How did you end up moving to Peoria?

In my second year of running the business, I met Bob Cohen from Peoria, who was at Harvard Business School. I helped him with his classes, because I had just completed that program. I married him after knowing him for only three months. We lived in Cambridge until my younger brother Michael took over the business, then we moved to Peoria.

Was that a big culture shock for you?

Yes, I can’t deny it. I had only been to Peoria once, to attend a party. When we came here in 1958, I was very sorry for a while, because I missed Boston. It was a whole different life moving here. I thought it was beautiful, but it was a culture shock for the first few years. But, I’d had a baby in Boston—my daughter Sheryl—and she kept me occupied.

How did you meet people after you came to Peoria?

When I was trying to decide where to go to school, my father said, “Smith College is the largest college for women in the country, and many of them are very active in their communities. No matter where you live or where you move in your coming life, you’re bound to meet somebody.” And he was right. My connection to Smith College helped me my whole life—especially when I came to Peoria.

I had the Smith connection with [community leaders] Sally Page and Harriet Parkhurst, who were very important to me. They took me under their wings. Harriet was my mentor—she immediately took charge and got me connected to the rest of the Smith women here. She knew what I needed, and she involved me in all of her activities. We raised money for scholarships for Smith, and I became treasurer for the project. Then I had my son Les, and I was involved in the usual school things—PTO, projects, and I was a Brownie leader at Kellar.

Peoria’s own Betty Friedan also went to Smith College. Did you know her?

Betty was ten years ahead of me at Smith and was best friends with Harriet Parkhurst. They graduated in the same class and were roommates in New York City before they met their husbands. When Betty came to visit Peoria, she would get the Smith group together and run ideas by us, asking for opinions about her projects from our perspective here in Middle America. It was an informal focus group of sorts.

Tell us about the beginning of your involvement in community service here.

I started with the YWCA—that was the first group I joined when I came to Peoria. Eleanor Connor got me involved, and she was another Smith connection. She was the mother of [banker] David Connor, who was a very important leader in Peoria.

My first project was to renovate the furniture and rooms in the downtown YW. Then Lois Carver and I co-chaired the building project at Lakeview. The YW had started the idea of developing that area. It was named “Lakeview” Park after the YW Camp across the river, which had a view of Peoria Lake. The Peoria Players building was built first, then Lakeview Museum [now the Bonnie W. Noble Center for Park District Administration] and the YW [now Lakeview Recreation Center], and finally the library and the Girl Scouts building. Those were fun years, exciting times.

When I was president of the YW board from 1973 to 1975, we had a capital campaign that raised over $2 million. We built a gym onto the Lakeview YW and did major plumbing and electrical repairs to bring the downtown building back up to code.

Why you were so passionate about the YWCA?

The women of the YW finance committee in those years were inspiring to me. They had a great devotion to the organization and its purpose to help women and girls cope with their lives. We hoped the families, in turn, benefited from our programs as well. Young women would come to the city to work and they could feel safe staying at the YW.

We also had a wonderful tea room downtown, and all the businessmen would have lunch there because it was so good. As a matter of fact, I think I got my first gallbladder problem from eating too many Viennese apricot pies, as that was their specialty!

The YW was pioneering in that time. They had the first shelter for women and a halfway house for women who couldn’t live alone.

What other groups did you get involved with?

I was involved in the Youth Farm League for decades. Youth Farm [now part of Children’s Home Association of Illinois] was a residential program to help youth change their behavior. When young men got into trouble, instead of putting them in prison or youth detention, they would take them to Youth Farm. Many were illiterate and couldn’t fill out a job application. Youth Farm was a very important organization in the community.

I also dreamed up “Hammerama,” which was a big fundraising auction and dinner for the Peoria Symphony Guild. At that time, my former college roommate’s husband was chairing a benefit auction for all of the arts groups in Hartford, Connecticut. It was a big affair every year—I think he gave me the idea for the name. There was an auction, and the hammer would signify when someone had won.

Bob and I went to their function in Connecticut, and I marched around in my cocktail dress with my legal pad and took notes. They had cars that were donated and brought them right out on the ballroom floor. So I took this concept and brought a whole list of ideas back to Peoria. Our auction was held at Expo Gardens, and we had over 630 people attend. Just like in Hartford, we drove cars right into the room next to the dinner tables. We raised a lot of money, and the next year they doubled it, and the third year they tripled it.

The Peoria Art Guild was another organization I was deeply involved with for decades. I was treasurer and then president of the board, and we had excellent shows. We copied the Art Institute’s sales/rental program and provided a real service of changing out art, as well as renting it to businesses. It was a wonderful program for people in the offices to understand how meaningful art can be. And when they bought what was on their office walls, it was a special treasure to me!

I was chairman of the Fine Art Fair for a couple years when we were still at Junction City. After my daughter Sheryl got married, she and [her husband] Michael went all over the country to different art fairs. They would scout the various artists they liked and pick up their business cards. They went everywhere. And Sheryl’s got a very good eye. [Esther stops to point out and describe various pieces of art in her home.]

Tell us about your work with the Peoria Civic Opera, which later became Opera Illinois.

Someone came to Peoria by the name of Cybelle Abt. She had been a singer in her youth and wanted to get the opera going here. I was very much in favor of that, as I had been to the opera in Boston, so I got involved.

Dave Connor found three friends to help support a dinner at the Creve Coeur Club, where they explained all about the opera, and then we all went to the Scottish Rite Cathedral to see Tosca. It was such a wonderful performance! After that I was called to help turn Cybelle’s private company into a community organization. Byron DeHaan [of Caterpillar] and I became co-chairs, and we had a very exciting first year of not knowing what would happen next. We just didn’t know how far we could go with this.

The next summer we put on Butterfly in Glen Oak Park. It was a spectacular success. Then the next summer we did Aida. Even the moon rose on cue during Aida!

Fiora Contino came to Peoria to conduct, and we had world-class opera here for 30 years. We wined and dined her, and she had a terrific personality. She was the conduit bringing wonderful voices to Peoria. She was a great professional and didn’t have a big ego, unlike many of her male counterparts. We were very lucky to have her! It was a pleasure to be involved with like-minded souls who felt that opera was important to their community’s culture and enjoyment.

One of your colleagues once called you “The Organizer” with a capital “O.” Tell us your secrets—how did you manage your committees?

I always tried to find just the right person for a project. I’d look around the room and look for the light of enthusiasm in someone’s eyes, and then I’d grab that person for the committee. Peoria is small enough so if you don’t know someone who can accomplish the job, then you know someone else who knows the right person.

I worked my tail off for things that interested me, and I hope my enthusiasm rubbed off. I always tried to keep it fun, and I fed volunteers whenever possible. My youngest daughter Jennifer learned early about meetings. When she was a baby, she’d pull chairs all around and when someone asked if she was playing school, she’d say, “No, I’m having a meeting.”

Did you try to instill the same values in your children as your parents did for you?

Yes I did, and it took! Especially art—all three of my kids love art. I used to sit Jennifer in a corner of the Guild with a coloring book while I was working. She and Sheryl and Les were always exposed to art. I dragged them through galleries wherever we went.

I also love historic preservation. I don’t know how you persuade people to save old buildings, but I certainly supported that whenever I could. I always wrote letters, which I felt was a very effective means of change. I still remember [former Congressman] Bob Michel saying to me that if he got 10 letters on a subject he’d look into it. So always write letters!

When you look back on your many experiences, is there anything that stands out as your greatest accomplishment?

You know, I have loved everything I’ve done over the years. We accomplished a lot—but a lot of it has gone away. The opera is gone. The YW is gone. Thank God I had those golden days! We did so much, and I was so proud of everyone who backed us. I have a wonderful sense of accomplishment and pleasure in being part of it all.

Right now I just want to put enough away for my children and grandchildren. [She pulls out a picture of her grandchildren to show me.] Julian is a sophomore and looks like his mother. Livia looks just like her dad. I look at them periodically because I don’t get to see them. I haven’t seen them in a year [because of COVID]!

Anything else you would like to add?

I think we all yearn for the simpler days of our youth. I liked getting involved in lots of stuff. I had lots of energy and was always very positive. But today, there are fewer people who can devote the kind of time we did back then. But we have to find a way to keep our cultural agencies going in Peoria. In a small town like this, it matters that everybody care—because we have an awful lot to do! PM