Kiran Velpula recalls being on stage at an event to raise funds for his research on brain cancer when a group of teen boys approached him.

“This group of kids had a cookout or something and raised $100. They presented me with that check and I asked why they did what they did. One of them said their dad had died of brain cancer,” Dr. Velpula said.

“Receiving that $100 check was one of the most touching things I’d experienced,” he said. “I feel the pain of family members who have lost someone to brain cancer. It really drives me in what I do.”

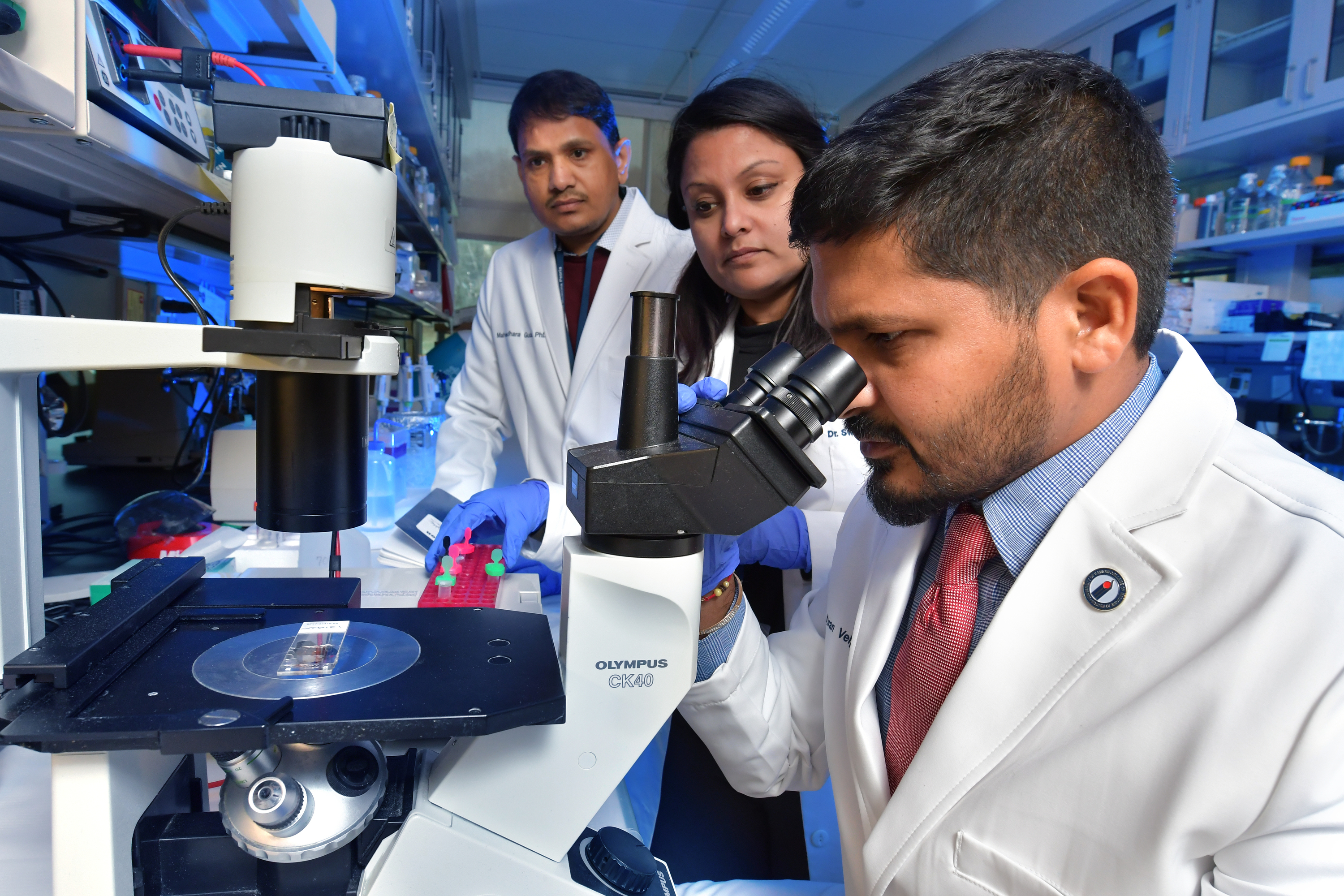

Velpula is an assistant professor in the Department of Cancer Biology and Pharmacology at the University of Illinois College of Medicine Peoria (UICOMP). His PhD expertise is in tumor metabolism, molecular biology, signal transduction and cancer biology.

For about 12 years, the research of Velpula and his research partner, Andrew Tsung, MD, head of the Department of Neurosurgery at UICOMP and director of Neurosurgery and Physiatry Services at OSF HealthCare Illinois Neurological Institute, has centered on glioblastoma.

‘It’s a black box. Cancer in the brain functions in a different way.’ — Dr. Andrew Tsung

Glioblastoma is the most common malignant brain tumor in adults and is also the most lethal. The average survival time is just 15 months, despite often aggressive treatment including surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. There is no cure.

Their research is partially backed by community support, including significant funding from the Mark Linder Walk for the Mind and the KB Strong Foundation. The not-for-profit organizations are named for Mark Linder, a Peoria native who died in 2005 after battling brain cancer for several years, and Kevin Brown of Washington, Illinois, the successful high school basketball coach who in 2019 lost his less than one-year fight against glioblastoma.

Over the years, the Mark Linder Walk has raised $803,000 for the Velpula-Tsung research efforts. To date, KB Strong has donated more than $151,000 to the cause.

The goal of Velpula and Tsung is to identify novel therapeutic avenues and develop small molecule inhibitors for the devastating tumors.

“We’re understanding how the cancer cells live and grow,” Velpula said.

The takeaways of their research, Tsung says, are difficult.

“We’re understanding how to stop the tumor growth and control facets of the tumor. It’s not like the movies when you hear about a ‘cure.’ It’s an arduous process and it’s incremental over decades,” he said. “We’re looking at cellular signaling and metabolism to understand a unique way for treating cancer. Most people think of killing cancer, but we’re researching to understand how a cancer cell can metabolize and shut itself down.”

They were the first team to show that Galectin-1, a type of animal lectin, interacts with carbonic anhydrase-IX in patients with glioblastoma. Targeting Galectin-1 in lab tests showed a significant increase in survival. Interestingly, Galectin-1 is a protein found in COVID-19.

Their research has resulted in the publication of 55 articles in journals such as Cell Death and Disease, Cancer Research, International Journal of Molecular Sciences and the American Journal of Cancer Research. Each published article reflects a “finding.” These findings help other researchers in their own work.

“They are small building blocks built upon one another and all of those are built on failures,” Tsung said. “We’re not going to come to the table in three years and say, ‘Eureka! A cure.’ The brain is especially hard to research compared to other fields of cancer. It’s a black box — it’s secured off from the rest of the body… Cancer in the brain functions in a different way.”

Currently, there is only one drug used to treat glioblastoma — temozolomide. The drug, Velpula said, kills the cancer cells initially but doesn’t prevent the tumor from growing back.

The partnership of a professor and a surgeon is uncommon, but both bring strengths to the lab. Tsung identifies problems he sees as he interacts directly with patients. Together they work toward solutions, along with their post-doctorate research specialist, Maheedhara Guda, PhD.

While their long-term goal is to develop new therapeutic drugs to control tumor growth, they have to first identify what the drugs will target, Velpula said.

“We’ve made a lot of strides in identifying novel targets that could be used to stop the progression of the tumor,” he said.

But he calls finding a cure or at least a drug to better treat glioblastoma a Herculean task.

“We are hopeful — we live on hope,” Velpula said. “But we’re also stubborn… Hope is always there.”