If leadership is about mentoring the next generation, then William Watkins, Jr. and Jacqueline Watkins are two of the strongest leaders Peoria has ever seen. During their 35 years running the Hersey Hawkins/Shaun Livingston Summer Basketball League, “Junior” and “Ms. Jackie” have impacted thousands of area youth, creating opportunities for others, just as others had done for them. The couple has been active with the Peoria Park District—with Junior serving on the Athletic Advisory Board and Jackie a 20-year member of the River City Soul Fest Committee—as well as People Helping Youth, raising funds to support youth baseball. They also coordinated international basketball and golf events for the Elks, with Junior serving as the organization’s Grand Athletic Director for two decades.

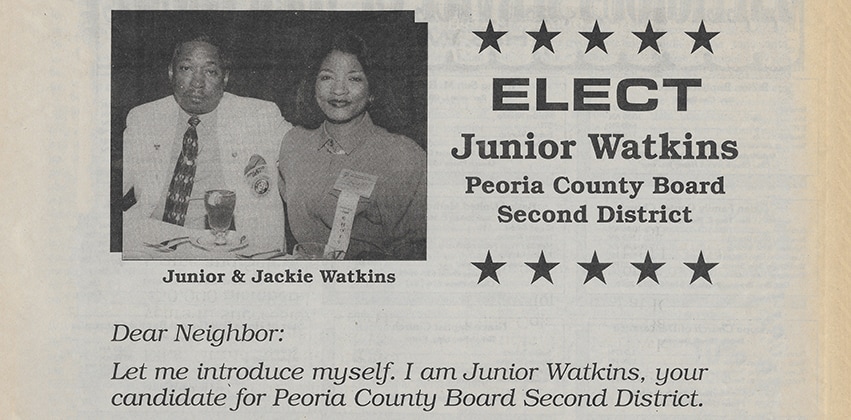

A former basketball star from Manual High School, Junior cofounded the Moonlight Basketball League and has been a volunteer official and coach for Caterpillar/UAW leagues and volunteer host for the IHSA state basketball tournament. He works at Brewers Distributing and has represented District 2 on the Peoria County Board since 1994, in addition to having served on the Peoria Fire & Police Commission and co-chairing the UAW Election Committee. Jackie is employed with the Illinois Secretary of State DMV and is an accomplished singer, lending her voice to the Heritage Ensemble, multiple church choirs, and a wide array of sports-related events. In 2018, the couple received the Neve Harms Meritorious Service to Sports Award from the Greater Peoria Sports Hall of Fame, which Junior served as a longtime board member.

As a founder and charter member of the African American Hall of Fame Museum, Junior helped lay a foundation to honor individuals who have made significant contributions to African American history, culture and society. More recently, he and Jackie helped lead the organization’s efforts to install the Richard Pryor statue that looms large over the legendary comedian’s hometown. They are members of New Cornerstone Baptist Church, and their life together has been one of dedication and purpose—getting things done, serving their community, and modeling excellence for the leaders of tomorrow.

Let’s start at the beginning. Jackie, are you originally from Peoria?

Jackie: I was born and raised in Decatur, but I had connections with Peoria. Decatur was a small town, and a lot of people had come up from Brownsville, Tennessee. The jobs brought them to Decatur because we had a factory called Wagner Castings and another called Decatur Malleable. When Decatur Malleable shut down, a lot of those people went to Peoria Malleable. Caterpillar and other jobs brought them here, and a lot of students who went to Bradley came from Decatur. So there was a real pipeline.

Did you know Preston Jackson and his family? [The Peoria artist was born in Decatur in 1944.]

Jackie: I grew up with him on the west side—his oldest sister is the same age as my mom. They all ran around together, and then we all ran around together. We were all real close.

What did you like to do as a kid?

Jackie: My dad was a math teacher and coach. As a matter of fact, he was Preston’s high school track coach. And I played sports… as much as girls could play back then. In the fifties they had the Brown vs. Board of Education victory, and the next year I went to Dennis School. I was the first Black to go through K-6 at my grade school, and I was the first Black cheerleader at my high school. I worked on the school newspaper and I was on the student council—first Black on that.

Did you have a sense as a kid that you were pioneering that integration?

Jackie: Yes, because my grandmother kept me so grounded… and because of the redlining and stuff. My grandmother and grandfather were strong in the community, and they kept me active in our church. My father was the first Black math teacher and coach at Stephen Decatur High School. It was just something that came. And never, ever, ever was it allowed to be used as an excuse.

The first day of kindergarten, my grandma said, “Now I’m not sure this is going to be okay, but the Lord has allowed it to happen. Sometimes association brings assimilation. And sometimes it’s good, and sometimes it’s not.” Some things were hurtful—everybody gets invited to the party but you don’t, or some of the kids can’t go because you’re gonna be there. You just forge on because you were raised to overcome those differences.

Going to college gave me another perspective of what was going on. I went to Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, and Indiana was Klan country. I didn’t have that with my white friends [in Decatur], but I was prepared for it. Some of the other kids never went to school with any white children. So when they got to college and were confronted by that kind of racism, it was traumatic. And for me, it wasn’t. I really appreciated that.

Junior, were you born in Peoria?

Junior: I was born in Newport, Arkansas. My parents brought me up here about 75 years ago, and I’ve been here ever since. I went to Washington Grade School on Moss Avenue, met a lot of very nice people… and that’s where I learned politics. I had to stay after school one night and they had a safety patrol meeting. Safety patrol would make sure you got across the street so the cars don’t hit you. They were getting ready to vote for captain, and it just so happened that somebody nominated me. I was just there to be punished. [Laughs]

How old were you at that time?

Junior: I was in the fourth or fifth grade. Somebody tried to be smart and said, “We’re going to nominate Junior Watkins.” And guess what? I won. [Laughs] I thought I was a big shot—walking around, checking the routes, getting out of school early… That’s how I got into politics.

Let’s backtrack a little bit. How did your parents end up coming to Peoria?

Junior: We had an aunt living here, my mother’s older sister, and she told us to come on up. We were very fortunate. We used to call her “Big Sister.” She didn’t have kids, so she just fell in love with me and my two sisters.

What are some of your earliest memories?

Junior: When I was coming up, you could walk all over Peoria any time of day. It made no difference… you could walk any place, stay out of trouble, and nobody would mess with you. I played sports in grade school, high school and college.

What were your favorite sports?

Junior: Well, my favorite was all of them! [Laughs] But I really liked basketball, and I ended up playing semi-pro. There was a guy named Clarence Faucett who was really good to us. He had all kind of leagues for us to play in—Pony League, Little League… We were blessed. Kids nowadays don’t always get the chance to do all that.

I played basketball at Roosevelt [Junior High] and then went to Manual [High School]. We were fortunate—Manual went to state my junior year. But a couple of the guys had turned 19, so they couldn’t play. [Nineteen was the cutoff age for eligibility at the time.] We just said hey, we’ll do the best we can. We ended up getting fourth in the state, without two of the best ballplayers on the team. There was a good chance we would have won state [with them].

What did you do after you graduated from Manual?

Junior: I went to Grandview [College] up in Des Moines, Iowa. When I came back home, my dad would get me a job at Armour’s packing house. I worked on the beef kill, where they slaughter the animals. I had a trolley to push and as the guys gutted the beef, they’d put it in the trolley. I stayed there for a while, and eventually I went to Caterpillar.

How long did you work at Caterpillar?

Junior: I stayed at Caterpillar about 18 years. I came out of the tool crib system. And by working in the crib, you meet a lot of people. One day I was talking to a couple of union guys, and one of them said, “Junior, you know quite a few people—you ought to run for something.”

So I started thinking. I said, “You know what, I would like to be on the Election Committee.” “Election Committee? Why do you want to be on the Election Committee?” I said, “Well, if I get on the Election Committee and you guys jack me around… I will get you.” [Laughs] So I was co-chairman on the Election Committee for UAW Local 974.

How did the two of you first meet?

How did the two of you first meet?

Jackie: We were both in the Elks—the Improved Benevolent Protective Order of Elks of the World. Junior was the Grand Athletic Director for the World—an officer of the whole international organization. They had a lodge here in Peoria, and we had a lodge in Decatur. And that’s how I met the infamous Junior Watkins! [Laughs] I had relatives in Peoria, and he was a big basketball star from Manual High School, so I had heard his name before. But he was a little ahead of me.

I guess fate kind of brought us to each other. The first time I went to the Elks State Convention was the first time we met. We had a lot in common, mainly sports. Later we got to talking and then dating, and the next thing I knew he asked me to marry him. We got married in August 1997 at the Elks National Convention in Louisville, Kentucky, in front of about 10,000 people.

Tell us a little more about your involvement with the Elks.

Jackie: The local lodges are community-oriented; it’s about giving back. We have a youth department and an oratorical contest at the local, regional, state and national levels—they give scholarships to the winners to help young people go to college. In fact, Oprah Winfrey was awarded that scholarship.

That was something that was large in the community back then. Somebody who worked in a factory might be the “Exalted Ruler” of the local lodge. It would give them some importance in the community—and leadership opportunities.

Junior, how did you end up working for Brewers Distributing?

Junior: It started with a fundraiser. Being so involved in sports, I wanted to do something for Clarence Faucett’s wife after he was deceased, because he had helped us out when we were kids. So we had a high school game and a college game for the girls and the boys… and I had to come up with a poster to put around the city.

I’d heard about Budd Jacob with Brewers—he had done a few things for the Elks. So I called out there one day. He didn’t think he could help because they had Budweiser posters, and we were dealing with kids and everything. Then he said, “You know what, we’ve got a Route 66 Root Beer sign—you can use that. Get as many posters as you want and bring me the bill.” After the fundraiser, I went and got a plaque and presented it to him. I really appreciated it because I didn’t have nobody else to go to.

A guy named Ted Arndt worked out there. He came to me one day and said, “Junior, Brewers don’t have any African Americans working for them; you might be in the running.” So I put my application in and Budd hired me right there on the spot. I was a PR guy—I did a lot with the public. I had everything on the south end [of Peoria].

How did the Hersey Hawkins/Shaun Livingston Summer Basketball League get started?

Junior: Budd came to me one day and said, “Junior, is there anything you want to do on the south side?” I said basketball’s been good to me—I would like to start a basketball league. He gave me $10,000 to get it going. I went and got the jerseys, put all the teams together, and we started off at Carver Center as the Budweiser Michelob Summer League.

That’s where Hersey and them started playing. At that time, we could get any ballplayer that played at Bradley. After he graduated, I asked if we could use his name to name the league after. He said, “No, Mr. Watkins, I don’t have a problem with that.”

Look at the guys who played in that league… Curley “Boo” Johnson. Shaun Livingston. David, Derrick and Daniel Booth. Jim Thome played when he was going to ICC. The coach at Richwoods, Will Smith, he played. Dan Ruffin from Central. Willie Coleman at Manual. The coach at Pekin, Matt Taphorn. Tony Wysinger at ICC. We had guys from all over the state coming here. The Douglas boys from Quincy—every Tuesday they would bring a team down to play. One of the best leagues they ever had in the state of Illinois outside of Chicago.

The best thing that happened to me was when my wife came to town! With the summer league, I was just doing everything… Then when she came along, oh, it got so easy! Everything I was doing, she would do with ease. Where I was struggling, she would just get it done, like [snaps fingers]. And all the guys were crazy about her. She knew everybody who came to town that could play ball.

That sounds like an amazing partnership! What was that like for you, Jackie?

Jackie: When we first got together, he said, “Well, I got this little thing that I do.” Little thing. [Laughs] Being into sports and all, I was just as excited as he was. Like I said, my dad was the freshman football coach, varsity track coach and the statistician for basketball. I was in junior high when they had all those good teams at Stephen Decatur High School, and I got to be on the bus with my dad. I was running the statistics… I wasn’t just there watching the cute guys play basketball—I was into it! And I knew about it. I think that helped a lot.

My main thing was being able to talk to the young men—the young Black men. Just like any of us growing up, we had our parents and everything, but there was always that auntie, or the little lady next door, or the choir director at church. There was always somebody you could have that connection with, who would just talk to you. You could ask them things you wouldn’t ask your parents, or talk about decisions you were trying to make. It was like they were my kids, you know? I always respected them, and I love the respect they had for me… They’d call me “Mom” or “Ms. Jackie.” It was always very respectful. And I loved being involved because it flowed over to the rest of the community.

My main thing was being able to talk to the young men—the young Black men. Just like any of us growing up, we had our parents and everything, but there was always that auntie, or the little lady next door, or the choir director at church. There was always somebody you could have that connection with, who would just talk to you. You could ask them things you wouldn’t ask your parents, or talk about decisions you were trying to make. It was like they were my kids, you know? I always respected them, and I love the respect they had for me… They’d call me “Mom” or “Ms. Jackie.” It was always very respectful. And I loved being involved because it flowed over to the rest of the community.

Then we started having the young men come over from Pekin, East Peoria, Metamora… and it was a mixing of cultures. It was good to see that fusion: “I can play with you, I don’t care if you’re purple… if you’re good, you’re good.” I could see that camaraderie, and they carried it on when they got to their college or university, feeling comfortable playing with each other.

And to see them go on… now they’re coaches and athletic directors and different things like that. One day Shaun [Livingston] came out and said, “Ms. Jackie, I want to help.” So we made it the Hersey Hawkins/Shaun Livingston Summer Basketball League.

So you’ve been able to stay in touch with a lot of the former players?

Jackie: Yes, especially if they stayed here. If there’s any connection they need or anything I can help them with, they come right on in. I’m so proud of all of them.

Junior, tell me about the Moonlight Basketball League. How did that get started?

Junior: The Moonlight League was started by George Jacob, Steve Shostrom, Phil Lockwood, Scott Meister and myself. Then Steve Turner and Matt Abraham were brought on as coaches. At that time Peoria was kind of shaky. Guys were fighting… gangs and everything. We came up with the Moonlight League to get them off the streets. They would play in the evening after everything had closed up. The rationale was to get everybody tired so they’d just want to go home and get some rest. [Laughs]

The best thing about Moonlight was when Hedy Elliott started the GED program. Some of the kids were scared to get up and say they needed a GED. I would tell them to just come in early one day, just slide on in, don’t tell nobody about it. You had to stay on them because they didn’t want anybody to know what they didn’t have. I said don’t worry, you’ll get it—just stick with Hedy. She’s gonna make sure you get it. She’s still doing that. She’s doing an outstanding job.

Jackie: Still carrying on that part of the Moonlight.

Junior, what prompted you to run for the County Board?

Junior: I was walking down the street one day years ago and saw [Chris] Duncan—he was on the County Board. He said, “Junior, I’m getting ready to give it up. Quite a few people around here know you… why don’t you run for it?” So I thought about it and put my feelers out. After I got in there, for years and years I had no opposition.

How did the African American Hall of Fame Museum get started?

Junior: I got in with some guys at Anheuser-Busch in St. Louis [through Brewers], and I was pretty tight with the Cardinals ballplayers. When the Cardinal Caravan came to Peoria, after the guys got done with everything they were doing, they came around with me. Willie McGee, Ozzie Smith, Vince Coleman… I took them all over the city. Never in my life paid for Cardinals tickets. [Laughs]

I was talking to a couple guys I worked with in St. Louis, and something came up about a Hall of Fame. They said, “Junior, that would be good for Peoria.” So I thought, I might as well go ahead and try. I grabbed just about everybody I knew… and said, hey let’s do something different in Peoria. We started off meeting at the library and ended up at Proctor [Recreation Center]. That’s how we got it together.

Preston Jackson’s statue of Richard Pryor, “More Than Just a Comedian,” was an initiative of the African American Hall of Fame Museum (AAHFM). Tell us about your involvement on that project.

Jackie: That was another Decatur connection: Richard’s grandmother is buried in Decatur. My mom and dad used to go to his shows at the Decatur Club. When Ike & Tina Turner came to town, he would be the opening act. I didn’t know him—Junior and his cousins did. I just knew that here was this outstanding comedian and actor who had come from humble beginnings. From here. Always mentioned Peoria. Always proud. But when I first came… there was nothing. You wouldn’t even have known he was from here.

I couldn’t understand that. Outside of Caterpillar, he’s one of the main reasons we’re on the map. For some people, that’s all they know about Peoria! Rev. Howard Johnson [AAHFM board president] felt the same way. We had been working and working on it, but there always seemed to be something stopping us. We said, we’re not going to give up on this. Because it needs to be. And Preston was like, I’m making the statue. We’re gonna do this right because this is Richard Pryor’s hometown.

So we got a committee together and put it under the auspices of the Hall of Fame—so it would be part of the nonprofit. We just worked to get that groundswell going and started pulling people in. They could see that it was really going to happen. We prayed about it a lot. Then we got all the big-name comedians together to raise the money. That was my Indianapolis connection, back to [comedian and Indianapolis native] Mike Epps…

Junior: The first time I saw Mike Epps, he had a comedy show in Springfield. I went to the show and one of the guys said to him, “Junior over there is from Peoria,” so he came over. He said, “You know anything about Richard Pryor?” I said yeah, he used to run around with my two first cousins. Back in the day you’d have thought they were in the Roaring Twenties! They’d put on the Al Capone suits and look like gangsters and everything—and they would trade suits every day! They’d have a suit on one day, the next day Richard had it on over here, and the next day somebody else had it over there. They said, “Junior, you want to join?” I said, “No, it don’t look like I would ever get clean!” All the suits were old and looked like they were ready to fall off. I never did see the clothes go to the cleaners! [Laughs]

Jackie: I told Junior, if they were involved, I could never be around—my stomach would’ve been hurting with them cracking on each other and stuff. So many of Richard’s experiences were, you know, Peoria experiences. And world experiences… how America was.

Did you know the “real” Mudbone? [Mudbone was one of Pryor’s most famous characters.]

Jackie: I’m pretty sure that was a combination of different people. And that’s what was so great about Richard—everybody had a Mudbone. That’s why it was funny. It was just like somebody you knew. I had respect for Richard’s story, what he had gone through. It was a good example of what you could get done, especially for the African American community.

What are you most proud of in your life and legacy, building these organizations in Peoria?

Jackie: First of all, it’s a blessing to be in those positions and for God to bless you with the things he does. To be with people and to be involved in your community… that’s what I’d say has been the best experience. And, the things I went through because God put me there.

You had to overcome so many more obstacles as a Black person in this country.

Jackie: My grandmother kept me grounded. She said, “My job is to make sure you have everything that you need. So when you go to school, you will be the same as them.” She made my dad get a credit card at Block & Kuhl so I could have the same clothes as the doctors’ and lawyers’ kids. She made sure I looked the way I was supposed to look… did everything I was supposed to do. So I couldn’t wallow around in anything.

I think that’s really what I am most proud of: just taking on these things. It taught me that anything can be accomplished if you do it with God’s guidance, with love, and with understanding.

Anything else you want to add?

Junior: Good leaders don’t necessarily seek to lead. They just do what’s right. PM