As life becomes increasingly virtualized in the year 2020, one might find comfort in the simple things. With screens seemingly triumphant over paper, the antiquated act of hand-writing a letter can be meaningful and even cathartic. To receive a handwritten letter is a joyous occasion, its sheer physicality conveying value that is absent from its digital counterpart. Even the common envelope can be a frontier of sorts in transforming everyday mundanities into personalized art.

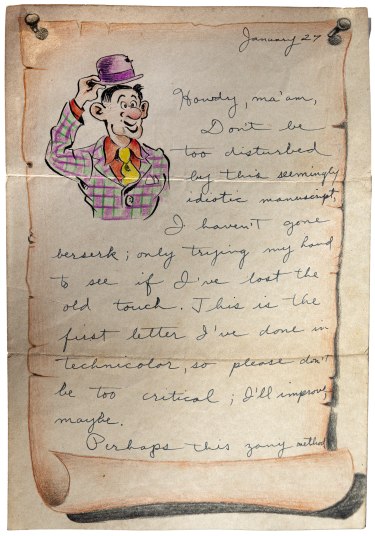

In the early days of COVID-19—when so many of us were learning Zoom, hosting virtual happy hours, and otherwise coming to terms with quarantine—Vicki Leunig Phillips rediscovered a family treasure. While cleaning out her office one day, she came across dozens of postmarked envelopes her father had mailed to her mother during World War II. Each was adorned with a hand-drawn, cartoon-like illustration—a rose-tinted window into the life and longings of a young officer in wartime.

Sharing some of these images on Facebook, Vicki challenged others to decorate and mail their own letters and envelopes to loved ones. “I decided that would be a rather novel way to reach out to my friends who use computers and phones, mainly, to communicate,” she explains. “As we were stuck at home with not a whole lot of stimulation, I thought this would give us an opportunity to share a bit of ourselves with friends and family.”

Letters From the Front

Born in Texas on December 26, 1923, Jeremiah “Jerry” R. Leunig was still a teenager when he joined the U.S. Army in 1943. At the height of World War II, he was following in the footsteps of his own father, who served during the first World War but had passed away four years earlier. Now living in Belleville, Illinois, with an aunt and uncle who encouraged his knack for drawing, Jerry’s creative talents flourished.

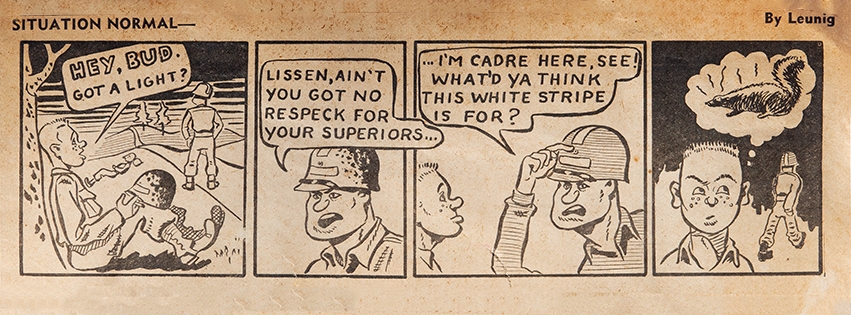

The vivacious Bettye Jeanne Murphy lived across the street, and she and Jerry attended high school together. They were dating, but not yet married, when he signed up to help fight the Nazis. While stationed at posts in Texas, Georgia and Alabama, Jerry drew cartoons for the base newspapers, portraying military life with his deadpan sense of humor—not unlike Beetle Bailey, whose creator Mort Walker had joined the Army the same year. The comical vignettes on the envelopes he sent to Bettye were an extension of these cartoons: a paratrooper being booted out of a plane, a hungry soldier chasing a milkshake, a lonely soldier dreaming of his sweetheart.

While Jerry served his country in uniform, Bettye worked at Scott Field (now Scott Air Force Base) outside of Belleville as a PBX operator, routing calls on the telephone switchboard, among other positions. Naturally she looked forward to the letters back and forth from her future husband. “They brought her a piece of the dry-humored man she sent off to the Army,” Vicki explains.

The couple married at Scott Field during the war—Jerry had come home on leave—and the envelopes he once addressed to Miss Bettye Murphy were now being sent to Mrs. J.R. Leunig. After the war, Jerry got into the advertising business, and the couple had two children, Vicki and Doug. In 1952, the Leunig family moved to Peoria, and Jerry opened his own ad agency. Amidst America’s post-war prosperity, he was a successful commercial artist for decades, producing all manners of ads, commercials, civic brochures and other creative content.

Precious Memories

Bettye Leunig kept Jerry’s decorated mailings in a scrapbook, so their children had always known of them. After she passed away in 2006, they fell into Vicki’s possession, a welcome memento of her parents’ romance and her father’s artistry. Among her earliest memories, at age four, is of one of his paintings—a black panther in a jungle-like setting. “His front paw was actually stepping out of the picture,” she describes. “The green eyes would follow you around the room.”

When Vicki went off to Camp Tapawingo, her dad would send her oversized postcards—hand-illustrated, of course. “The one that I remember best showed an oversized mosquito chasing a Girl Scout,” she recalls, “very reminiscent of one of his envelopes to Mom.” Naturally, Jerry’s creativity trickled down to his children.

“I was nine years old when he had me pose for a picture with a grocery bag on my head,” recalls Doug Leunig. “He used a Polaroid instant camera, which was new technology. Not only was the one-minute, peel-apart picture fascinating to see, he used it as reference to draw a picture of a full-grown man wearing a chef’s hat. It was magical to see myself transformed by his ability to draw.”

“I was encouraged as a toddler to draw and create,” Vicki adds. “I made flipbooks and dioramas in shoeboxes, drew clothes for my paper dolls, and was always creating something. Daddy liked to carve, and I would too, with my trusty Girl Scout knife. He created clay figures for his ads, and I would create things out of modeling clay.” She also remembers decorating letters and envelopes to mail to her grandparents—“definitely influenced by my dad.”

Creativity Paid Forward

Creativity Paid Forward

Early in life, Doug won a prize for an original cartoon he had drawn—an event which helped to ignite his own artistic path. After a 30-year career as a corporate photographer, he retired from Caterpillar Inc. and turned his attention more fully to the arts, seeking to pay his rich childhood experiences forward. In 2018 he and his wife Eileen cofounded the Big Picture Initiative to offer creative opportunities to others in the Peoria community. His late father Jerry Leunig, Doug’s first role model in the arts, would surely be proud.

Like creativity itself, Jerry’s influence was significant in ways both direct and indirect. “Being around the creative mind gave me the idea that creativity is a natural part of life,” Vicki suggests. “It also helped me to think outside the box when I came up against something that was unusual or challenging. I would look at the problem from all sides, figure out what I want to achieve, design what steps I needed to take to get from here to there, and then go for it!”

Perhaps there are circumstances more unusual or challenging than the onset of a global pandemic. But in this age of social distancing, it’s easy to see how the personal touch of a handwritten letter could be a balm for loneliness, its artistic flourishes an antidote for isolation. Amidst a relentless digital cacophony, it’s no wonder the notion of “happy mail”—that is, snail mail which is neither a bill nor junk mail—has become a growing trend.

Several friends took up Vicki’s Facebook challenge, decorating their own cards, letters and envelopes and mailing them to loved ones. They, too, are talismans of human connection, as Jerry and Bettye Leunig well knew, to be discovered and treasured by future generations. PM