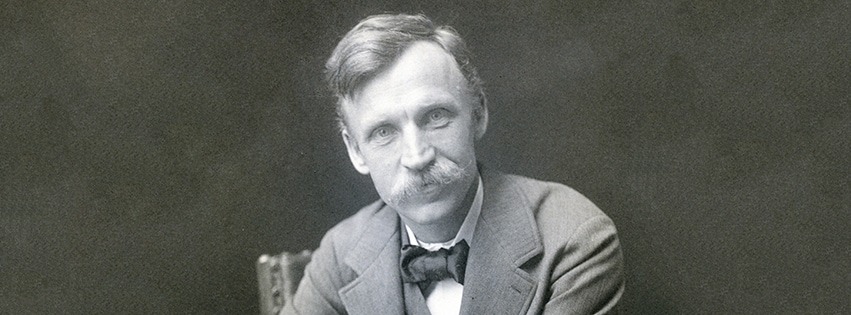

Before electric media arrived on the scene, Americans relied solely on the printed page—books, newspapers and magazines–for information about their world. That was certainly Samuel Sidney McClure’s world after graduating from Knox College in Galesburg in 1882.

S.S. McClure showed an affinity for information-gathering and the printed page while in school, founding the Knox Student, the school newspaper. “He swept through Knox in a whirl and went on in a blaze of business acumen and progressive zeal to help change the country for the better,” wrote David Amor, a member of the Knox faculty in a memo to promote a campus program on McClure in 2003.

“By bringing the muckraking exposes of [Ida] Tarbell, [Lincoln] Steffens and others to the American people, he fueled progressive reforms, made a fortune for himself, elbowed his way onto the Board of Trustees, and eventually died penniless, to be buried here in Hope Cemetery,” Amor continued. That whirlwind summary reflects the life of the man often cited as the king of the muckrakers in the era of reform journalism in the early 20th century.

Tackling National Issues

S.S. McClure didn’t set out to be a reformer, according to Peter Lyon, McClure’s grandson, who wrote a biography about his grandfather in 1963 entitled Success Story: The Life and Times of S. S. McClure. “He was not himself, properly speaking, a reformer,” Lyon told Studs Terkel, a McClure admirer, in a radio interview in 1967. “He was an editor who wanted to publish well-written, well-documented material about matters that concerned the nation.”

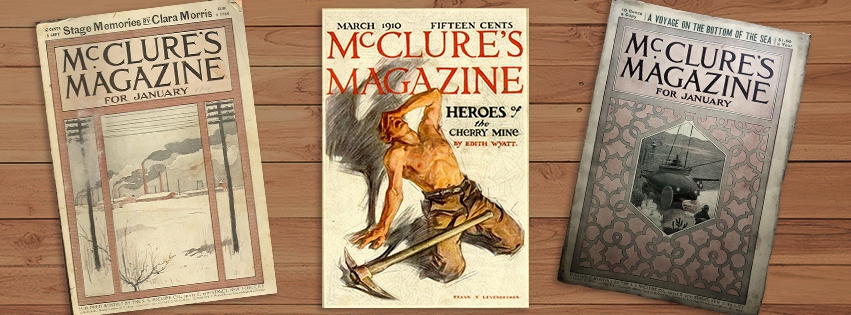

Matters that concerned the nation in those days were Big Oil in the form of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, corruption in the cities, and the railroads, notorious at that time for fixing rates despite government oversight. All of these—and many other issues—were tackled by McClure’s Magazine, the monthly publication that McClure ran from 1893 to 1912.

It was a golden age for magazines, which benefited from a growing, more affluent population and improved print technology. Often cited is the January 1903 issue of McClure’s which, along with the usual fiction, poetry and artwork, contained three distinct muckraking articles: the third chapter of Ida Tarbell’s 19-part history of Standard Oil; “The Shame of Minneapolis” by Lincoln Steffens, the latest in his “Shame of the Cities” series; and Ray Stannard Baker’s article on how non-striking coal miners were treated in Pennsylvania.

The stories were the result of painstaking planning and straightforward reporting—concepts that were at the heart of McClure’s magazine methodology.

Yet even before he organized the magazine, McClure did something even more extraordinary: he started a syndicate. Two years out of college, McClure decided to develop a company to supply stories to the nation’s growing number of newspapers. Others had thought of the same thing—buying material from writers and then turning around and selling it to newspaper publishers.

Lyon pointed out the difficulties his grandfather faced in accomplishing that feat. “It is not easy to imagine a less promising commercial undertaking than the McClure syndicate at its outset,” he wrote. “[McClure] had less than $25 in the bank, no capital to buy the stories he proposed to sell.” But through sheer energy and enterprise, he was able to succeed, raising the level of literacy in the American press in the process.

Jet-Setting Ideas Man

McClure may have initially lacked capital, but he packed the gift of gab and an editor’s eye for talent as he crisscrossed the country to find writers. But he didn’t stop there. Between 1887 and 1893, he made eight separate trips to Europe. The roster of writers he worked with reads like a who’s who of literature: Stephen Crane, Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson, Jack London, J. M. Barrie, Booth Tarkenton, Willa Cather, Edna Ferber, Arthur Conan Doyle and Joseph Conrad are just some of the authors with whom he did business.

McClure’s efforts allowed American readers to sample works by Stevenson, Barrie, Doyle and Conrad for the first time. His ability to recognize writing talent and subjects important to readers carried over to the magazine that he began planning in 1892.

It should be noted that another Knox College alum played a role in creating the magazine that became a platform for muckrakers. John S. Phillips, a classmate and close friend of McClure’s who had come to work on the syndicate (after initially advising him against it), provided $7,300 worth of capital. His physician father mortgaged and rented the family house in Galesburg in order to raise the money.

Money may have helped McClure start the magazine, but it wasn’t what made him go. In his biography, the advertising manager at McClure’s, Curtis Brady, is quoted as saying, “I cannot think [McClure] ever gave money a thought except that more income would make it possible for him to spend more money for features and fiction for the magazine.”

To call McClure an “ideas man” was probably an understatement. As William Allen White, one of the many outstanding journalists who worked for McClure’s, noted, “Sam had 300 ideas a minute, but [Phillips] was the only man around the shop who knew which one was not crazy.”

Among the ideas McClure conceived was having Mark Twain serve as editor of the magazine (with McClure running things, of course). A considerable amount of time was spent trying to convince the celebrated author on the benefits of such a collaboration.

As the jet-set magazine editor of the early 20th century, McClure lived life large. After he sailed for England in 1903, Lyon describes a typical itinerary as “a night with Kipling, a lunch with Conan Doyle, another with Joseph Conrad,” followed by a swing around the continent: Berlin, Geneva, Paris.

McClure’s passion for travel, suspected affairs and a carefree indifference to financial matters might have worked out so long as his erratic behavior was balanced by editors like Phillips and Tarbell. The duo, however, finally became frustrated trying to rein in the boss. They departed to start another publication, The American Magazine, in 1906—the same year other staff members (including Steffens and Baker) left the magazine. Things were never the same.

Out With a Bang

Despite the mass defections, McClure was still able to edit a solid publication that continued to sell on the newsstands. Willa Cather was now on the scene, adding her literary expertise to the cause (as well as ghostwriting McClure’s autobiography), but the magazine’s financial problems continued. Without a watchful overseer to help steer the ship, McClure found himself forced out as editor of the publication that bore his name in 1911.

McClure carried on, introducing an American audience to the Maria Montessori teaching method when the two launched a U.S. speaking tour together in 1913. The magazine plodded on in various forms with various owners, and McClure even found himself back as editor in the 1920s. But it wasn’t the same. He may have been editor in title, but he wasn’t calling the shots and soon drifted away.

McClure died in 1949 at age 92 and was buried in Galesburg next to his wife Hattie, who had died 20 years earlier. “Galesburg was not his home but, after all, there really was no place that had been his home,” related Lyon, who concluded the book on his grandfather with this: “His Galesburg friends remarked that on the day of his funeral, the town was struck by the worst cyclone in its history. S.S. McClure, they agreed, went out with a bang.” PM