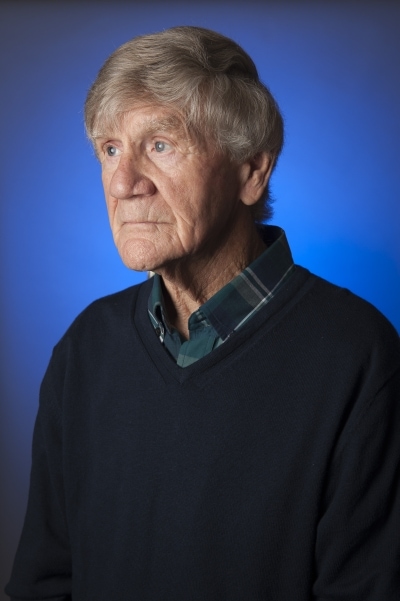

Photography by David Vernon

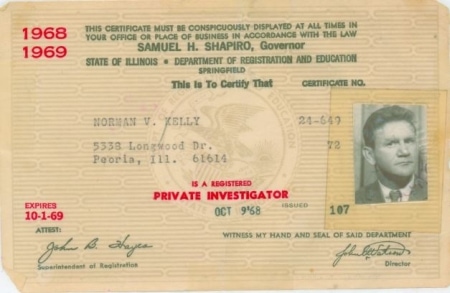

If you want to know about old Peoria, Norm Kelly is your guy. A lifelong Peorian of Irish ancestry, he’s spent decades researching and writing about his hometown… and he didn’t really get started until mid-life. A distinguished alumnus of Woodruff High School (though he claims to be “the worst student they ever had”), Norm served in the U.S. Air Force during the Korean War, before returning to his hometown and graduating from Bradley University. For 20 years, he was a licensed private investigator doing undercover work for attorneys and insurance firms, “outsmarting everybody” and getting into all sorts of outlandish situations, which proved useful fodder for his later storytelling.

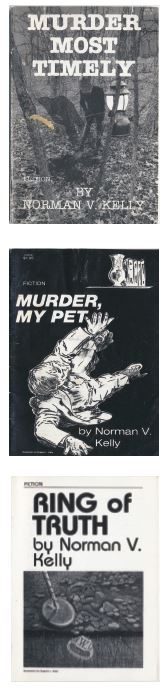

Unemployed at age 50, Norm started running—and that’s when his writing career really took off. He’s since written a dozen books and more than 600 short stories and articles, from true crime and murder mysteries to historical accounts of his beloved Peoria. He’s written often of the city’s “seedy and bawdy” era, yet was equally determined to debunk the myths of gangsters and speakeasies that arose over the years. And he’s donated much of his literary proceeds to local causes like Children’s Hospital of Illinois, Peoria Public Library and Habitat for Humanity.

While chronicling the stories of Peoria policemen who died in the line of duty, Norm discovered five fallen officers who were never recognized for their sacrifice. Thanks to his painstaking efforts, their names are now etched onto monuments in Peoria, Springfield and Washington, DC. Likewise, he later learned that the first Peorian to die in the Korean War was never honored—and today, Pfc. Luther Bernard Zimmerman’s name is engraved on the memorial plaque outside the Peoria County Courthouse. Paying tribute to these fallen patriots, he says, has been his life’s proudest achievement.

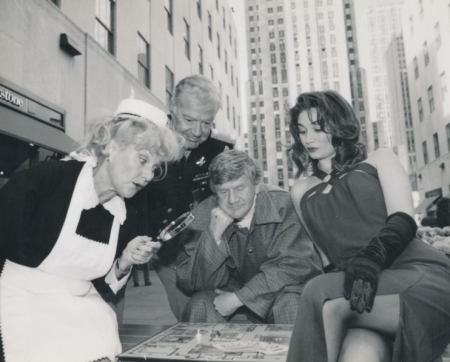

A longtime member of the Mystery Writers of America, Norm has been a frequent guest on radio and TV, and he was once even crowned the U.S. Clue champion in New York City—despite never having played the game. “The truth is, I’m just a local yokel,” he says. “I don’t have an interest in any place but Peoria.” Norm and his wife, Gloria, have one son, Keith; a daughter, Lynn; and two grandchildren—Samuel and Brooke.

Norm, can you paint a picture of life growing up in El Vista?

It was a brand-new subdivision in Peoria County. We moved there in 1937, and eventually, there were 13 of us—11 children, plus mom and dad. We moved in on Albany Avenue. The house was at the back of the lot, because my dad was going to build this big house out in front. That’s what we thought forever, but it burned to the ground in 1950.

I want you to picture this little house, with no bathroom. It has an attic—not finished, of course. One bedroom for my mom and dad, my three brothers were in another, and we had a kitchen and a living room. Upstairs were all the rest of us. When the wind blows and the snow comes, we would hug that chimney to stay warm. We had a water pipe that came up in the kitchen, and it froze in the wintertime. We had no indoor plumbing; we were in total poverty. And if you think that doesn't destroy you as a child… Really, it really does.

I didn't think I was lucky. I didn’t think life was wonderful. Everybody else had what I thought were nice teeth, a perfect smile… things like that. I thought that if you were a millionaire, you lived forever. I connected health and everything with having money.

I survived by running into the woods when I was eight or nine, to Schmoeger Park. I was an outdoor person. I loved the creeks and the trees… The people I ran around with, we were extremely compatible. But if there was any trouble to get into, I started it. And if there was any way to get out of it, I got us out of it (laughs).

What led you to join the service?

I was living with my uncle and working at R.G. LeTourneau Company, a neat little job in the supply department. Maybe you need a stapler or something—we made sure we got it to you. We’d put safety posters up on the wall, ride around the plant… it was just fun. We got to see R.G. once in a while. I wrote a wonderful story about him later.

Then the [Korean] War came along. So I go with my friend Henry Cvik, and we join together. We go down to Texas and go through basic training. I was a smart-ass, and 114 pounds—just the minimum. If I was 112, they wouldn't take me. But I got in.

Why did you choose the Air Force?

My brother Dale was in the Air Force. My brother Gene was in the Navy, and Bud was in the Army. Dale was a fighter pilot during World War II. In the Korean War, he flew an L-9, but he never really made it anywhere. In my mind, he should have been a major. My wife's brother, however, became a general, and I wrote about him. But my point is: I was always trying to look for somebody to look up to.

Then this sergeant came along, and he was a tough guy. But I knew he wasn’t—he was just playing a role. I got in trouble with him, mouthing off, and he picked on me pretty good. In the end, I got a stripe in boot camp. Ask any G.I. you ever met if he got a promotion during boot camp… he’d laugh in your face!

How did you manage that?

This guy grew somehow to admire me. Then I realized all these things were his way of testing me, working on me personally. I took a battery of tests, and they assigned me to the Navy and sent me to surgical school. Now, you're talking about the worst student Woodruff probably ever had! (laughs)

So you were in basic training for the Air Force, but they sent you to the Navy?

Yes, they called it TDA: temporary duty assignment. They sent me to the naval station up at the Great Lakes, and I went to their dental surgical school.

Norm Kelly, front row, fifth from left

What were your expectations when you joined the military?

Absolutely no expectations. I knew not everybody flew airplanes; I knew you had to be an officer. So what would I do? I didn’t even know. I just went in.

Did you want to get away from Peoria?

Not Peoria. I just wanted to get away… I wanted to do something. I'm a very patriotic, red-blooded American. I loved the war. I led scrap drives and paper drives… You’re looking at someone who believed John Wayne and the propaganda—how great we were. And I wanted to be one of them.

How influential was World War II on you as a kid?

Best time in my life. Isn’t that strange? Don't forget: when the war started on December 7, 1941, three weeks later, it's ‘42. People forget that. 1941 was a magnificent year in Peoria. Our population had just passed 100,000. And when the war came along, it was the best thing that ever happened to us. Isn’t that horrible?

Because more people were working?

You bet. And more than 22,000 people went off to war, including my three brothers.

So how did you end up in dental surgical school?

When you get out of flight training, your whole life goes up on a board, and they're going to assign you somewhere. So you're looking at the board… This guy’s going to electrical motor school in Denver, Henry's going to MP school, and Norm Kelly is going to the United States Navy.

I end up on an airplane to the Chicago area, and I go on board the largest naval training station in the world. And I was assigned to this college; I think it was 16 weeks or so. Then I graduate and they send me to the Azores—nine islands, 2,400 miles from Boston, give or take—a military air base. The Cold War is going on in Europe, and we're fighting a war in Korea.

Many of our soldiers were injured in training and all kinds of tank accidents… They were treated there. They had to be flown in—there’s no other way to get there. Over in Korea, we were being killed—52 died from Peoria. But the point is: now I’m at an essential base, I’m assistant to a captain, and we did essential work.

So you helped him with surgeries?

Yes, but that didn't come in the beginning. When I was there, it was a dental clinic. But when these Air Vac airplanes came in… These patients were injured and burned, casualties. The sergeant came to me and said, Corporal, we're going to assign you to the ambulatory. I had no idea what he was talking about.

They were all Section 8 [“mentally unfit for service”]. He said, Norm, when these ambulatory patients come, they will be in shackles. I didn't know anything, but I don't stand there and have a big conversation. I learn everything.

So when the airplane pulled up—a big C-97—I take out the 30 ambulatory people in shackles. I was in charge of getting them up in the bus and looking after them. I would talk to them and keep them in line. That was extra duty—it had nothing to do with the fact that I was a surgical technician.

We had to watch them all night long. And there were noises in there—it was scary… One night I feel this hand coming right over my shoulder… and it didn't have a shackle on it. Scared me to death! He was looking for a pack of cigarettes, which I didn’t have. And then two of them got loose! Thank God, not while I was on.

But we would feed them and take care of them, and then they would go to Westover Air Force Base for further treatment.

You’ve said that you learned to be a storyteller in the military. How did that come about?

You’ve said that you learned to be a storyteller in the military. How did that come about?

I was defending my hometown. I didn't like the idea the SOBs thought Peoria was a gangster town—that was how it started. I would meet somebody, from Belleville, Illinois or somewhere: You're from Peoria? And they would start telling me [that]. I’d say what the hell are you talking about? Where did you get that? So I’d begin telling them good things about Mayor Woodruff. I was basically defending myself and the city of Peoria.

Did you ever meet Mayor Woodruff?

They would have rallies, and I was there with my dad. He would make fiery speeches. If Mayor Woodruff was not our mayor, he was running for mayor. If he wasn't running for mayor, then he was negotiating and doing all the things that he did. He had a place called the “Bum Boat,” a piece of junk up the river, and he would [meet with] the Democrats and Republicans… Well, you’ll do this, and he'll do that, and he will be the treasurer, and so on. And it was all Mayor Woodruff—most powerful man in Peoria’s history.

Mayor Woodruff, he was 100-percent Peoria, Illinois. I always admired him.

Was he on the take? Of course not—and that's the part people can't believe. They used to draw cartoons of a truck being backed up, giving him money. Giving him money? For what? He had all the money in the world. He owned an ice company and a fish company. He was brilliant and hated and loved and despised and respected. He knew every soul in town worth knowing. He'd come to your bar mitzvah, and go to a Catholic mass, and show up at your uncle’s house. I mean, he was Peoria, Illinois, for better or for worse. And believe you me, he led us through everything.

In 1920, he said to the world: we're going to open our taverns back up, and I'm going to offer a soft drink parlor license. The most important thing that ever happened to Peoria was that simple act… because we were dying.

Because of Prohibition?

August of ’17—that's when they shut down the distilleries and breweries. Most powerful man on earth was Wayne B. Wheeler [Prohibitionist and leader of the Anti-Saloon League]. No one even knows who he is [today]. It wasn’t until January 16, 1920, that they shut the taverns down.

We were doomed, this city was. Now, I’ll tell you the magic number: 28,636—that's how many people moved into Peoria during Prohibition. That's the secret of the city…

So they were here to get “soft drinks”?

They were “confectionaries.” You could take your wife and kids, and have a doughnut and a 10-cent root beer or Coke. But of course, with a shot and a half of Canadian booze!

How did you end up going to Bradley?

My colonel said, Norm, have you thought about matriculating? Of course, that means to enroll in a college. I said hmmm, what’s that mean, Colonel? I know about Bradley, he said, it’s a wonderful school. And I said no, I haven't thought about it—I'm no college student. He said, what are you talking about? You passed everything, look at you! And you can get out almost a month early, Norm. So what are you going to do?

I wanted to go back to Peoria and get my job back at R.G. LeTourneau. He said, where’s that going to take you? I don’t know. He said, well, you don't know where a college education will take you either, do you? I said no. So that's what I did.

Were you working then?

Oh yes, and I graduated in three years, because I went [to school] around the clock. I worked third shift at Hiram Walker, cleaning glue and stuff off the machines. When I graduated, I went to Retail Credit Company. They checked on people who request… kind of expensive insurance—to see what kind of person you were. That's when I got into the investigations.

So your schooling had nothing to do with becoming a private investigator…

No. But I got a degree. I started out as a claims person for the insurance company, then became an adjuster. And then I met an attorney named Tom Cassidy. My friend said to him, you know, you really should think about hiring Norm Kelly—he's the best investigator around here. And Tom said, really… And that's how I got my license: registered private investigator.

Now I’m a licensed investigator and paralegal. I was a whiz at it and met tons of people—who all ended up in my books.

I did that for almost 20 years. Personal injuries, divorce… I found missing people and served people nobody else could serve. I was always outfoxing, outmaneuvering [people]… I even used my young son once. I had to serve this nurse; she was about to skip town for Texas. So I went to her apartment, rang the doorbell and hid. When she looked out, all she saw was my son. She opens up the door and says, are you alright? And I touched her on the shoulder with that subpoena. She said, I’ll be a son of a… But we had to have her. If she’d have gotten to Texas, we’d have never won the case.

And then finally, he had to let me go. Now I'm unemployed at age 50. Fortunately for me, I got a phone call from Dr. [Donald] Rager. He's director of medical affairs at OSF, as high up as you can go. He says Norm, would you consider working as my assistant? He's respected, brilliant… and he was fascinated by what I did and how I did it.

So I became his administrative assistant—a paralegal and private detective, working at OSF. And I said Don, what are you going to do with me? He said, you'd be surprised. He couldn’t do anything I could do, and I was not going to be a doctor! (laughs) I was the “shadow man,” doing background checks, criminal checks, all kinds of things. I recruited physicians, and we brought in some magnificent people. I also ran across some horrible things—people would lie, even child molesters. I uncovered them by going into police records all over the United States. Then I became claims supervisor; I did the medical malpractice claims for OSF. And then finally, I quit at 62.

How did you get started as a writer?

How did you get started as a writer?

I wrote a story when I was in the service. It was pathetic. I didn't show it to anybody. That’s when it started. But I didn't really start writing until I was 50.

When I was unemployed, I started running… and I just wondered, what am I going to do? It was snowing and I saw these two dogs. They looked like wolves to me. They were running; then they stopped and looked at me, and scared me. I just kept running. It was out by Detweiler [Park], a magnificent night. They were on the other side of the street, but they appeared to be running with me—I had that impression. So I came home and wrote “Running with Wolves.”

Then my boss, Dr. Rager, bought me a typewriter for Christmas. He said, Norm you’re a helluva writer. I began to write these stories, and they're all mysteries and murders. I wrote 12 stories, and my brother Gene [compiled] them in these little booklets. Then they all went into a book called Murder in Familiar Places.

What was your connection to [former Bradley basketball coach] Dick Versace?

I knew him well. My wife Gloria worked at Bradley, and his assistant lived across the street, so we got to be close. Dick read one of my stories, and he said to me, Norm, you can really write. Why don't you go see my mom? His mom was [author] Tere Rios—she wrote [the book that became] The Flying Nun.

So I went up to Rhinelander, Wisconsin to meet this brilliant lady, and she immediately liked me… mainly because I was a friend of her son. That Friday, she calls me in. She has all my work there. And she says, Norm, you can't write. I’m sorry.

I just stared at her. She says, Norm, you're the best storyteller I’ve ever seen.

She said you were a great storyteller, but you can’t write?

Can’t write. There's so much wrong with this, Norm. What should I do? Well, keep writing!

She said, I'll tell you what I'll do… When you go home, you start sending your stories to me. And she would help with editing.

Now at work, I have an electric typewriter, and sometimes I go in at night to write. And for the first time, I would really read these stories and realize, you know, that’s good! I know what I’m doing. But I don't know how to do it.

As time went on, she was less and less critical. She’d say, Norm, brilliant, brilliant! Where’d you get that plot? I could never have done it [without her].

How long did you work with her?

Those first 12 short stories. When I got them done, I dedicated a book to her and my brother.

And the characters in your books were based on people you’ve known over the years?

Yes. And I really knew how to plot. I had all this basic knowledge. I enjoyed having the bad guy be the smart guy, and that guy was always me. I put myself in most of the murders.

Tell me about the national Clue contest that you won in 1986.

“Clue-do” was the name; it was for members of the Mystery Writers of America. So I entered, and I won. Think about that. I was up against “real” mystery writers… now I'm the United States Clue champion. Clue. Never played the game in my life!

So they invited me to New York City. I met [crime novelist] Mickey Spillane and he said, “Norman Vale Kelly… what a magnificent name.” Mickey Spillane! I met actors … Jay Thomas, who played on television and in the movies… I'm sitting in a tub on Park Avenue, and we have limos. This is a big deal. The Journal Star is following me around, writing about me, and we're having a wonderful time. We even met Bosley, you know from that TV show [Happy Days]? Tom Bosley.

So they invited me to New York City. I met [crime novelist] Mickey Spillane and he said, “Norman Vale Kelly… what a magnificent name.” Mickey Spillane! I met actors … Jay Thomas, who played on television and in the movies… I'm sitting in a tub on Park Avenue, and we have limos. This is a big deal. The Journal Star is following me around, writing about me, and we're having a wonderful time. We even met Bosley, you know from that TV show [Happy Days]? Tom Bosley.

So I’m in the pool. This man [Jay] Thomas gets in and says, you’re Norm Kelly, aren’t you? I said, how do you know that? He said, well, you're in the New York Times! And then back in Peoria, they were writing stuff: “World Champ? Kelly hasn't a Clue.” And it ticked the ad agency off. Here's a guy, he won the contest and never played! Well they didn't catch on, because Norm's a lot smarter than they were! (laughs)

You know what I did when I got off the airplane? They said, we'll see you at the airport, Norm; we'll pick you up in the limo. I got some straw and put it up in the lapel of my suit. So I get off the airplane and walk up to them, and we shake hands. And they see this straw. They don't say anything, but they see it. Finally, we’re in the limo and the lady looked over and said, Norm, is that straw? I said, well, I guess I must have worn my suit out in the barn!

And right then, they knew [I was joking]. The guy said, we don't have a farmer here, do we, Norm? (laughs) I said no, we don't.

So tell me about your book Officer Down, and the police officers who were killed but never honored.

I found five police officers killed in the line of duty who were never honored. I researched it for a year, and I discovered one officer—the first [Peoria] police officer who died in the line of duty—wasn't on the monument. And I wondered, why wasn’t he on there? I wrote this incredible story about him… and I began to realize. There was a scuffle… and the cop was killed in the fight. But the jury exonerated [the killer].

Well of course, I knew the truth. He should not have gotten into this fight. But he did, and he died in the line of duty. And when the time came to honor him, somebody said no. And who was that? It was the captain. I exposed all of that.

Needless to say, when I got done with them, they regretted it, believe me. Then it was in the newspaper, a massive story. The reason they didn't do it was because the jury found the killer not guilty, so they thought he was beneath them. They were letting the damn jury decide whether or not he was on the monument! And it pissed me off.

When did that happen?

When did that happen?

1894, Patrolman Theophil Joseph Seyller. And if you go down to City Hall, right there it is… the one that's all by itself.

The other four I found… I called them “The Forgotten Four.” They were all killed in the line of duty, all Park District [Police] who were never honored. I got the Landen [Volunteer Service] Award from the Park District and a state police award… which made me feel good, because I brought them out of absolute obscurity and put them on a monument. That was a big deal: phone calls, television and radio wherever I went. I even ended up on America's Most Wanted. I got invited to DC, and 30,000 police officers and their names are right on the monuments. And now the ones in Peoria were on there, too.

How did you decide to become a historian?

Because these guys in the service thought my town was such a horrible gangster town. And I couldn't believe it. I was here!

So I started looking at the newspapers. I went back to 1828—that's when the first steamboat comes chugging up—and read all the way to 1951. Now you know why I’m blind! (laughs)

Let me tell you what I did when I wrote Lost in Yesterday's News. It starts in 1920, Prohibition, and I created the famous private investigator, Chauncey “Chance” Coogan. I thought this was the most wonderful thing—that I can just create a character… and there he is. He wasn’t a private eye—it was me, made up and put into 1920, all the way through 1950. He tells you everything. And everything he says is absolutely historical.

“Chance” Coogan. He's smart, and meaner than hell, but he has this wonderful softness to him. He had this feeling about Peoria, and this need—this absolute need—to tell the truth about it.

I spent all those years researching stories about who we were—including our “gangster period,” when the Sheltons, came here. I know who Bernie Shelton was. He lived over at 707 Monson [now William Kumpf Blvd] with his wife, under the name of Bernard and Genievieve Paulsgrove. I spoke to at least two dozen people who knew the man, who liked him. Never, ever could I find a story I wanted to tell you about Bernie Shelton.

Don't you think I would want to write [about it]? Well, there was nothing to write about him. What do you mean, Norm? He was a gambler. Some of the best, top-notch businessmen in the city were gamblers! Mayor Woodruff was a gambler, but not much. He was a drinker, but not much. But he knew everything and everybody. He knew that there will always be vice—but let us make sure they pay for the privilege. And every dime of it is right there for you to look at! It’s in the record.

So part of your motivation in telling these stories was to dispel some of the myths?

Exactly. iBi